URBAN reduX

Abstract

URBAN ReduX studies the transformation of post-pandemic office districts into resilient, socially balanced urban ecosystems. Conceived as an Advanced design-research studio at the Bernard & Anne Spitzer School of Architecture, the project reframes conversion not as an isolated real-estate tactic but as systemic adaptation—linking building morphology, policy, energy infrastructure, and community formation. The work deploys field mapping, code and FAR analysis, and AI-assisted typological modeling to diagnose how millions of unused square feet might evolve into mixed residential, cultural, and production space. It argues that conversion should generate public value: daylight, access, and social reciprocity. Architecture functions here as urban metabolism—processing the surplus of capital into spatial commons.

Context

When New York’s central business districts emptied during the pandemic, the vacancy appeared statistical, yet its meaning was civic. Roughly 26 Empire State Buildings’ worth of space stood idle, translating economic overcapacity into spatial inertia. URBAN ReduX positions this condition as an inflection point in the life of the skyscraper city. The modern office tower—optimized for floor-plate efficiency, sealed envelopes, and elevator logic—no longer matches the flexible, distributed economy it once served.

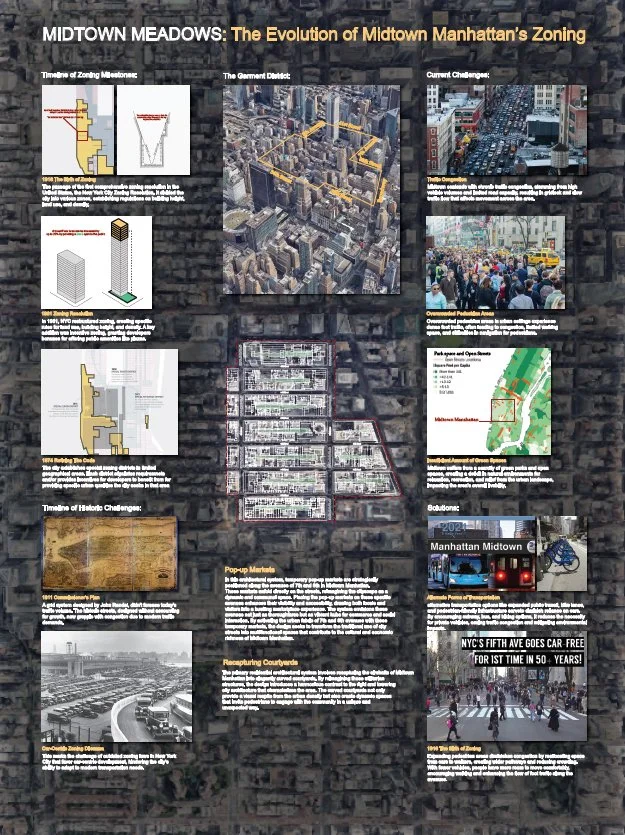

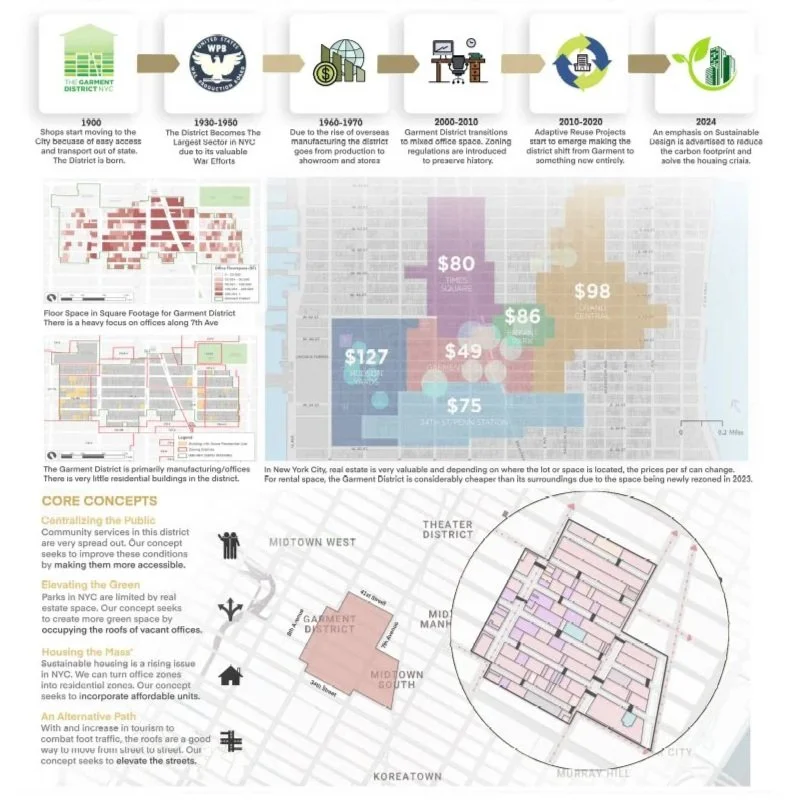

The studio begins by tracing this misalignment historically: from 1916 zoning setbacks that sculpted light-seeking towers to 1980s deep-plate efficiency models and 2000s sealed glass systems that prioritized rentable depth over livability. The post-COVID transition to hybrid work exposes the ecological and social cost of those assumptions. Energy systems run half-empty; ground planes fail to support street vitality; small businesses that once depended on daytime density collapse. Vacancy becomes both environmental waste and opportunity.

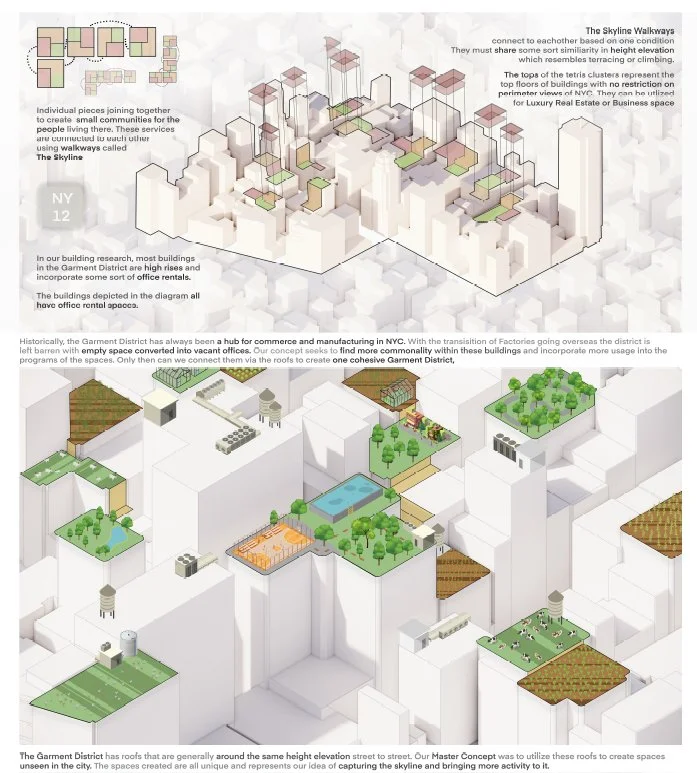

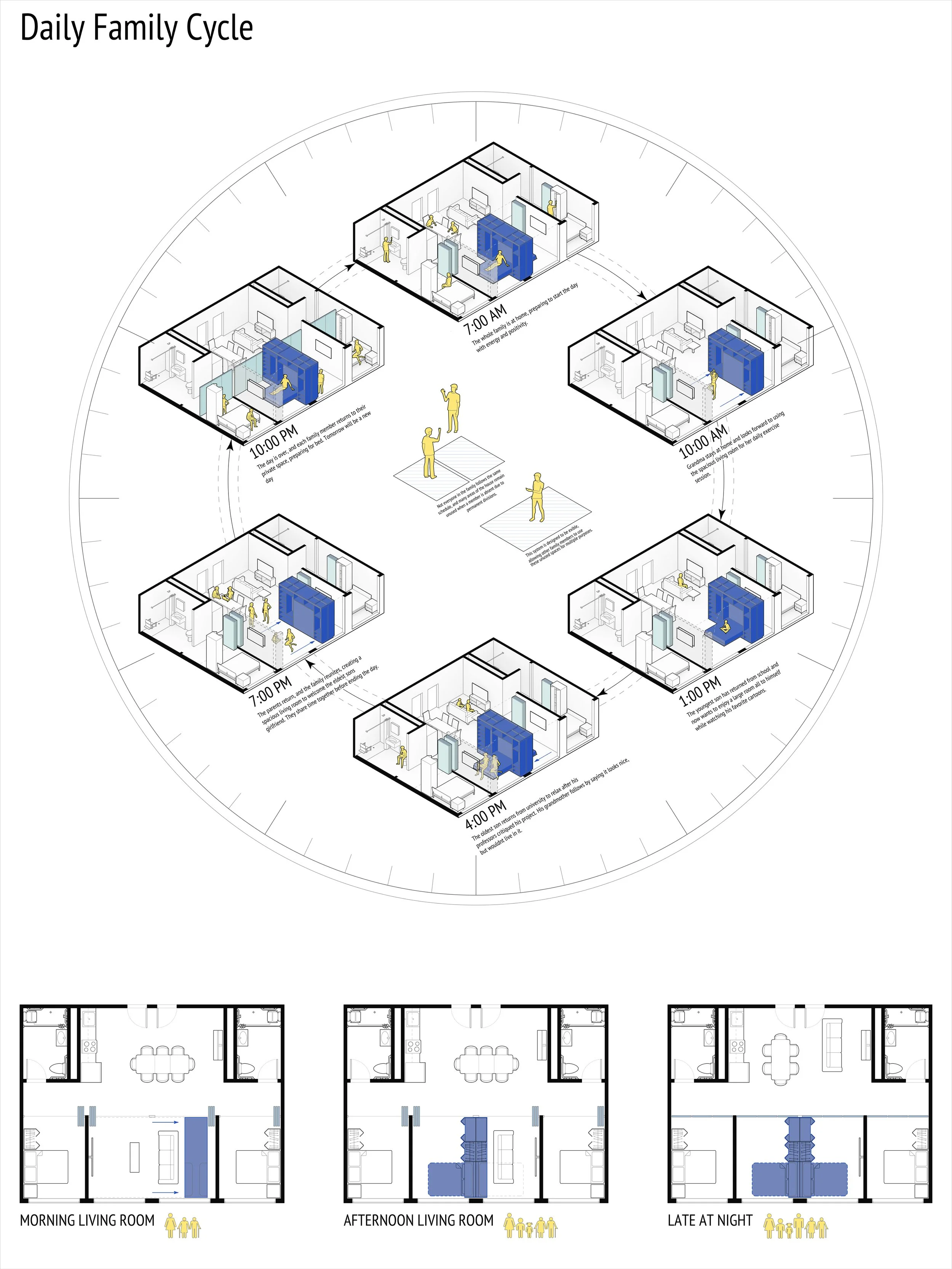

URBAN ReduX reads Manhattan’s empty offices as latent infrastructure. Instead of pursuing isolated conversions, it investigates how clusters of buildings could be retrofitted into continuous, service-linked districts that combine living, making, and learning. The guiding question—what are the ingredients for a community?—grounds the design agenda in daily use rather than speculative density.

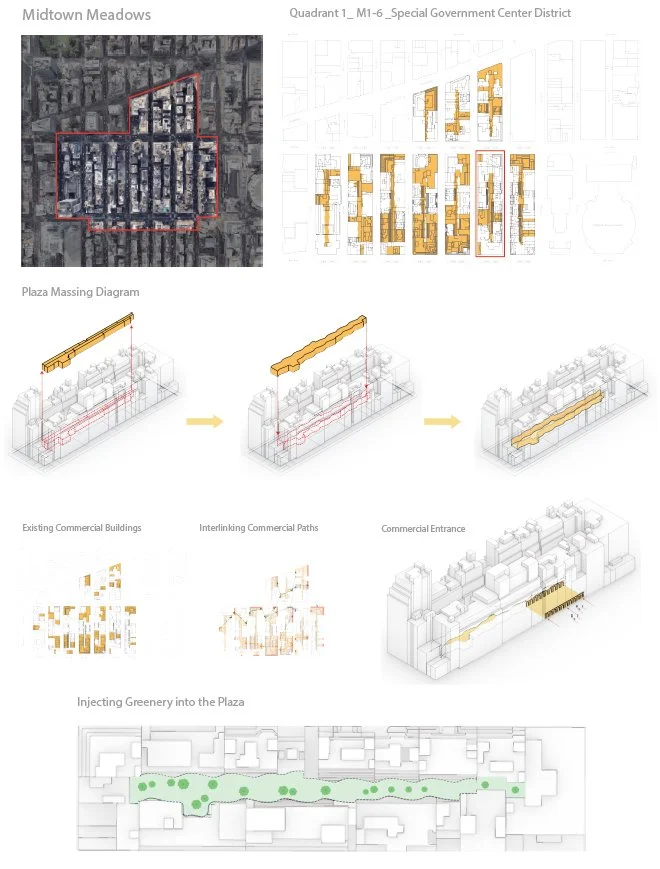

Two pilot geographies anchor the study. In the Flower District, narrow lots and mid-rise warehouses suggest fine-grain, mixed-tenure housing and craft studios. In Midtown East, monolithic office slabs demand new daylight apertures, structural subtractions, and vertical courtyards. Across both, the research insists that transformation must address not only form but governance: incentives, ownership models, maintenance responsibilities, and public access.

The contextual reading extends beyond architecture into policy. Zoning relief, energy-upgrade credits, and adaptive-reuse funds are treated as spatial instruments. The project links civic agencies, private owners, and community boards into a cooperative framework where conversions yield measurable reciprocity—affordable units, public rooms, gardens, and transparent operations.

Methods

The research organizes its work into four linked methods that translate surplus floor area into civic capacity.

1. Inventory and morphology

The first step builds a policy-grade inventory: plate sizes, core depths, structural systems, glazing ratios, setback and light-plane constraints, elevator counts, egress, and MEP risers. These attributes are tied to feasibility flags (e.g., plates under a threshold depth; cores that support split egress; column grids compatible with residential spans). At the block and district scales, teams map existing open-space deficits, school and clinic catchments, transit access, and logistics corridors. Morphology is read as coupled with services: not just “can it convert?” but “what does it connect to?”

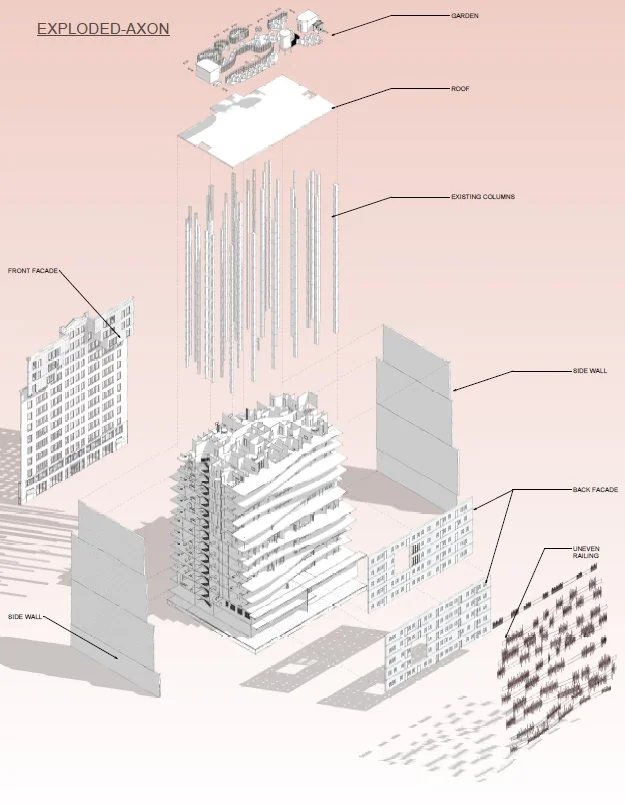

2. Conversion typology and program ecology

The studio defines a family of conversion types, each with structural and service preconditions: slice-and-court (recapture daylight via mid-plate voids), shaft-unlock (reorganize core and risers to create dual-aspect units), frame-plus (add lightweight top-up or interstitial mezzanines), and hybrid basements (activate deep floors with non-residential programs—fabrication, clinics, schools). Programs are developed as ecologies—housing coupled with ground and roof commons, childcare, teaching kitchens, and repair workshops—so that residents, workers, and visitors co-occupy overlapping infrastructures.

3. Governance and delivery protocols

Design is paired with governance instruments: how ownership, incentives, and stewardship align. The method identifies levers—zoning relief tied to affordable quotas, expedited permits for envelope upgrades, tax credits for water/energy retrofits, and community benefit agreements that secure publicly accessible terraces and rooms. Procurement is framed as design: maintenance cycles, replacement part standards, and the assignment of responsibilities (building vs. tenant vs. city) are documented alongside sections and plans.

4. Tools and accountability

AI-supported sketching accelerates scenario generation but is constrained by explicit prompts, data citations, and iteration logs. Student booklets and decks demonstrate how metrics (e.g., FAR shifts, unit mixes, daylight factors) accompany drawings, turning proposals into replicable protocols rather than isolated visions. The studio culture is investigative: each claim about livability or performance is traceable to a measured condition or documented rule.

Findings / Reflection

1. Vacancy is a system, not a symptom

Treating empty offices as isolated failures leads to scattered pilots and minimal urban effect. Mapping reveals pattern: deep plates clustered around certain eras of construction; corridors of obsolete stock near transit but far from schools or parks; redundant elevators paired with underperforming ground planes. The finding is that conversions must move in coordinated clusters to rebalance access to light, air, and services—unit-by-unit fixes cannot repair district-level deficits.

2. “What are the ingredients for a community?” is an architectural brief

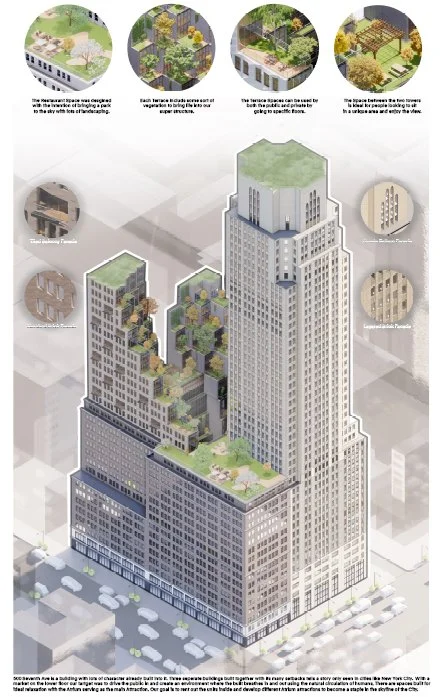

The studio insists that community is not a vibe but a set of spatial and operational conditions: places to meet unplanned; kitchens and making rooms; terraces and gardens that host daily rituals; routes that invite encounter without erasing privacy. Housing alone cannot carry this; ground floors, roofs, and mid-building commons become the connective tissue. In practice, this means dedicating usable area to shared rooms, and writing maintenance and stewardship into the base building pro forma.

3. Recapturing light creates both livability and legibility

Student proposals that “recapture air shafts as courtyards” point to a broader principle: daylight is a public good inside the block, not a private amenity at the facade. Slicing plates to create interior courts improves unit quality, cross-ventilation, and wayfinding while enabling vertical micro-commons—narrow gardens, laundry terraces, or reading balconies. The cost in gross area is offset by reduced mechanical loads and higher long-term value. The street learns to read conversion from these incisions: a new urban morphology made visible.

4. Hybrid programs stabilize conversions

Offices rarely convert cleanly to 100% housing. Deep floors and low daylight factors at lower levels are better suited to community-serving programs—clinics, training kitchens, fabrication labs, performance spaces, micro-warehousing—than to bedrooms. Pairing these uses with housing above stabilizes occupancy across dayparts and supports local employment. The result is a mixed metabolism: services anchor social life and lower operating risk for owners by diversifying revenue streams.

5. Governance is design in slow motion

Many conversion barriers are legal and financial rather than tectonic. Relief on light and air, reclassification of egress and elevator loads, incentives for high-performance envelopes, and clear pathways for adding shared rooms are as architectural as any detail. URBAN ReduX treats code analysis and procurement planning as drawings in another register—diagrams of responsibility over time. The ethical claim is that architects have agency in these domains when they make the rules legible and negotiable.

6. AI accelerates seeing, not deciding

The studio’s use of AI-generated sketches demonstrates speed without surrender: prompts encode constraints; outputs are reviewed against measured conditions; and selections are documented. In this format, AI functions like a fast pencil that exposes options early, raises blind spots, and reduces iteration waste. It does not choose; communities, data, and governance do. The benefit is cultural as well as procedural: students learn to pair synthetic imagery with empirical accountability.

7. Nature-in-the-city must be operational

Green walls, roof gardens, and street planters appear throughout the booklets, but they are framed as systems: rainwater capture and greywater reuse that reduce combined-sewer loads; shade and evapotranspiration that lower cooling demand; biodiversity corridors that stitch terraces to streets. Planting schedules, irrigation, and access for maintenance are specified alongside species lists. The measure is not greenery as image but ecology as service, tied to a custodian and a budget line.

8. Street economies migrate upward through deliberate edges

Where ground floors open into interior streets, pop-up markets, and learning rooms, small-business agency and cultural life follow. Escalators and stair voids extend the sidewalk into the building; glazed fronts and shared seating create “overlap zones” where commerce and commons mix. This is not a mall transplanted into an office shell; it is a civic gradient where informal economies can surface, test, and stabilize. The edge—sill, stoop, arcade, loggia—becomes the city’s negotiator at multiple levels.

9. Conversion is a lifecycle, not an event

The most robust proposals design for change. Demountable partitions align with grid and services; replacement parts are standardized; envelope and systems are chosen for maintainability; operations manuals are drafted with inspection intervals. These decisions make conversions reversible at component scale and adaptable as demographics shift. A building’s usefulness is measured by how well it can host the next program without demolition.

10. Equity is a performance criterion

If vacancy is a citywide cost, its relief should produce citywide benefit. The studio’s emphasis on affordable/student housing overlays, shared amenities, and publicly accessible terraces points toward reciprocity. Incentives should return value as access: free rooms for community groups, discounted stalls for local vendors, internships tied to on-site training, and transparent governance boards. Architecture, in this reading, mediates fair exchange rather than merely enclosing new rent.

11. Districts matter more than icons

URBAN ReduX keeps the camera wide. Conversions clustered near schools, transit nodes, and parks compound benefit; isolated gems do not. Block- and corridor-scale plans—where multiple owners coordinate cores, voids, and shared services—unlock morphologies that one parcel cannot deliver. In a system city, district design is the only scale at which conversions add up to community.

12. The public question remains the guide

The refrain “What are the ingredients for a community?” stays active by design. It is answered not by slogans but by rooms, routes, services, and rules. The findings across sites suggest a pattern: shared kitchens and learning rooms; terraces that hold daily rituals; edges that invite encounter; operations that are transparent and trusted. Conversions succeed when they deliver these ingredients in legible, maintainable form.

Credits

Architecture Field Lab Research Program: Shamina Chowdhury, Ismael Cajamarca, Ashley Gordon, Elan grabarnik, Selbi Hasanova, Angel Hidalgo, Juan Valen, Grace Lombardo, Noor Muzahid, Yasmeen Navarro, Jaydin Parker, Daniel Susan, David Tzalik, Taseem Kahman

Collaborators: Spitzer School of Architecture, John Cetra, Nancy Ruddy, Joan Krevlin,

Location: Manhattan (multiple office districts and corridors)

Year: 2023–2025

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com