Territorial Typologies

Abstract

The project investigates how architecture interprets the spatial, political, and ecological dynamics of migration at Mexico’s southern border. Developed within the CCNY Integrative Design Travel Studio led by Martin Stigsgaard and Ali C. Höcek, the research studies how the movement of people, resources, and institutions produces evolving territorial typologies. These are understood not as fixed forms but as adaptive systems shaped by law, landscape, and logistics. The work treats migration as both humanitarian and architectural: a condition that reorganises ground, time, and attention. Through mapping, fieldwork, and speculative design, the study tests how architecture can act as a mediating tool that translates data into empathy and policy into inhabitable structure. The inquiry positions architectural practice as an agent that reads systems, exposes relationships, and proposes precise spatial adjustments that expand dignity and capacity.

Context

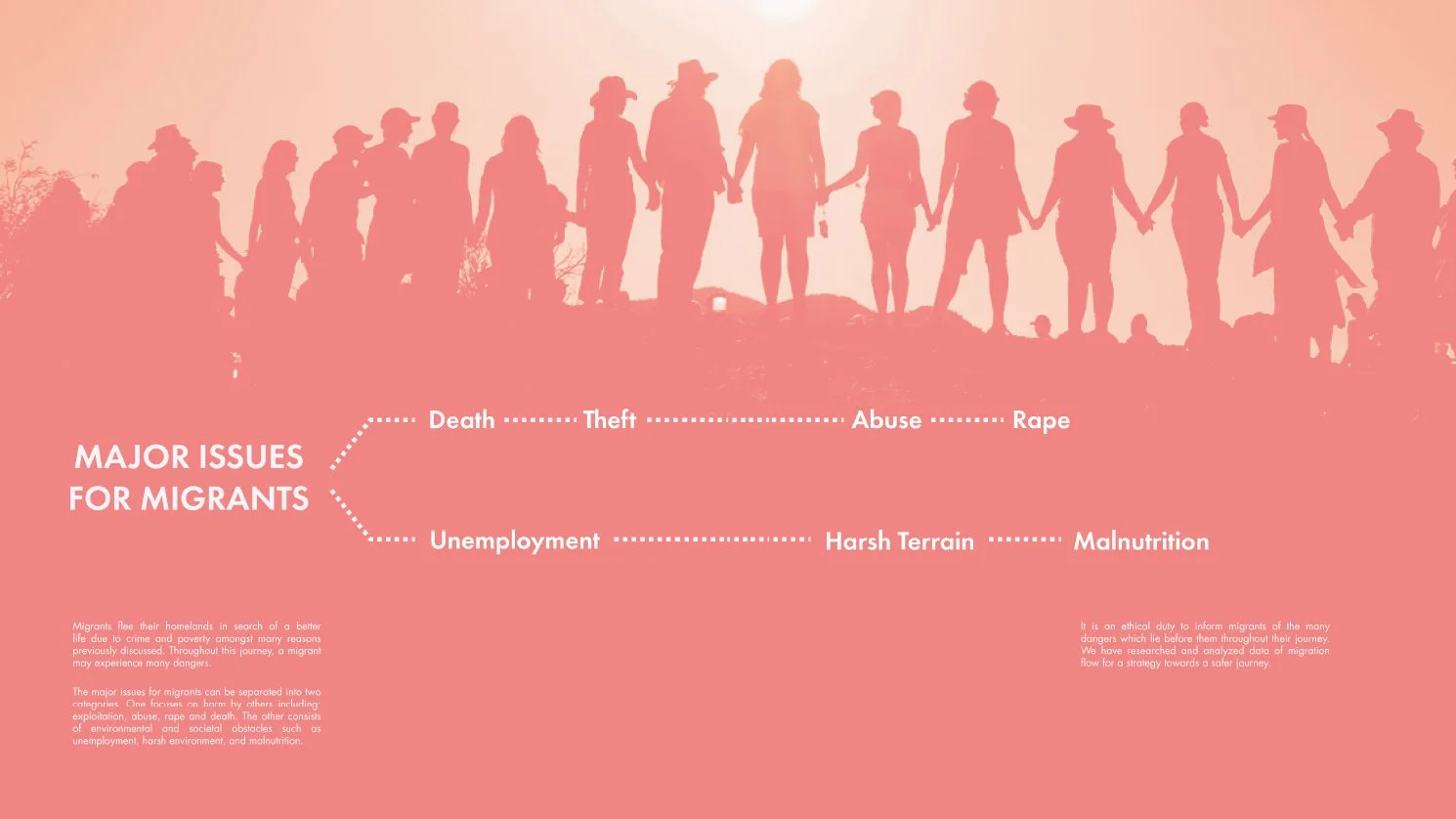

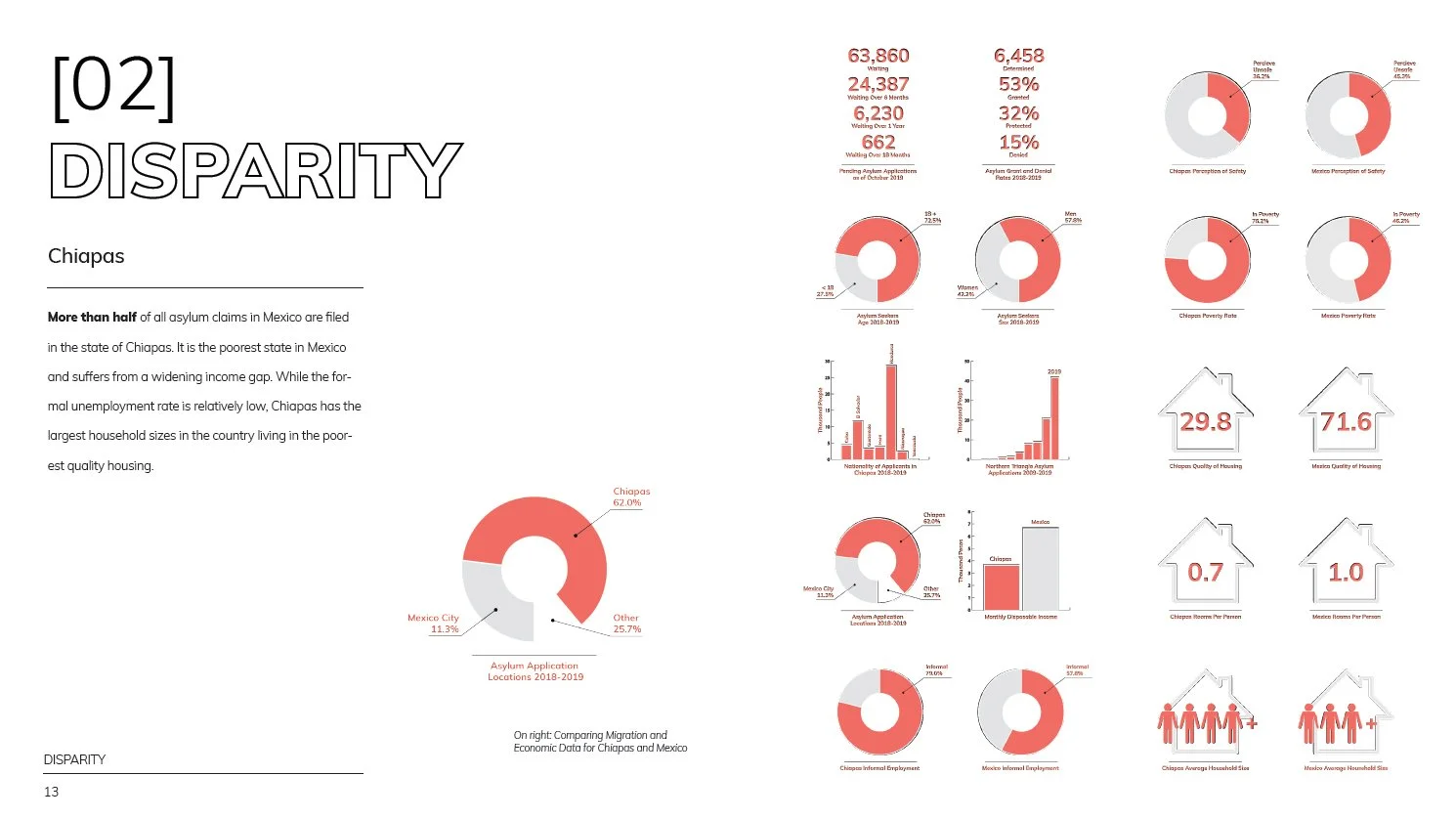

Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala is a layered environment where international policy, local economy, and river ecology converge. Tapachula, in the state of Chiapas, functions as a hinge in this geography. It is a site of entry, delay, and redistribution. The Suchiate River marks the border in plan yet remains porous in practice: formal checkpoints coexist with informal crossings, seasonal rafts, and agricultural paths. Migrants arrive from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, West Africa, and South Asia, carrying distinct legal statuses and needs. The apparatus that receives them includes federal agencies, municipal services, the International Organization for Migration, faith‑based shelters, and neighbourhood networks. Each actor produces space: lines for registration, yards for waiting, dormitories for rest, kitchens for shared work, and classrooms where rights are explained.

Tapachula’s urban fabric mirrors these layers. Logistics corridors support commerce while residential districts absorb intermittent surges in population. Abandoned warehouses become temporary dormitories. School courtyards host vaccination campaigns. A single plaza can act as marketplace, protest ground, and informal recruitment site. The border is therefore less a line than a distributed territory that expands and contracts with policy change, weather, and news cycles. Conditions of heat, rainfall, and flash flooding interact with bureaucratic schedules to shape daily movement. These factors give the territory a cadence that is measured as much by paperwork and buses as by kilometres and bridges.

Within this evolving context, the studio’s collaboration with the International Organization for Migration, the Jesuit Refugee Service, and local NGOs anchors the research in lived experience. Guided visits to information hubs, shelters, and river crossings foreground the sensory realities of migration: noise levels that prevent rest, glare that impedes reading, and circulation gaps that cause bottlenecks. These details carry ethical weight. The project frames them as design problems tied to agency and care.

Methods

The methodology follows five linked phases that convert observation into spatial intelligence.

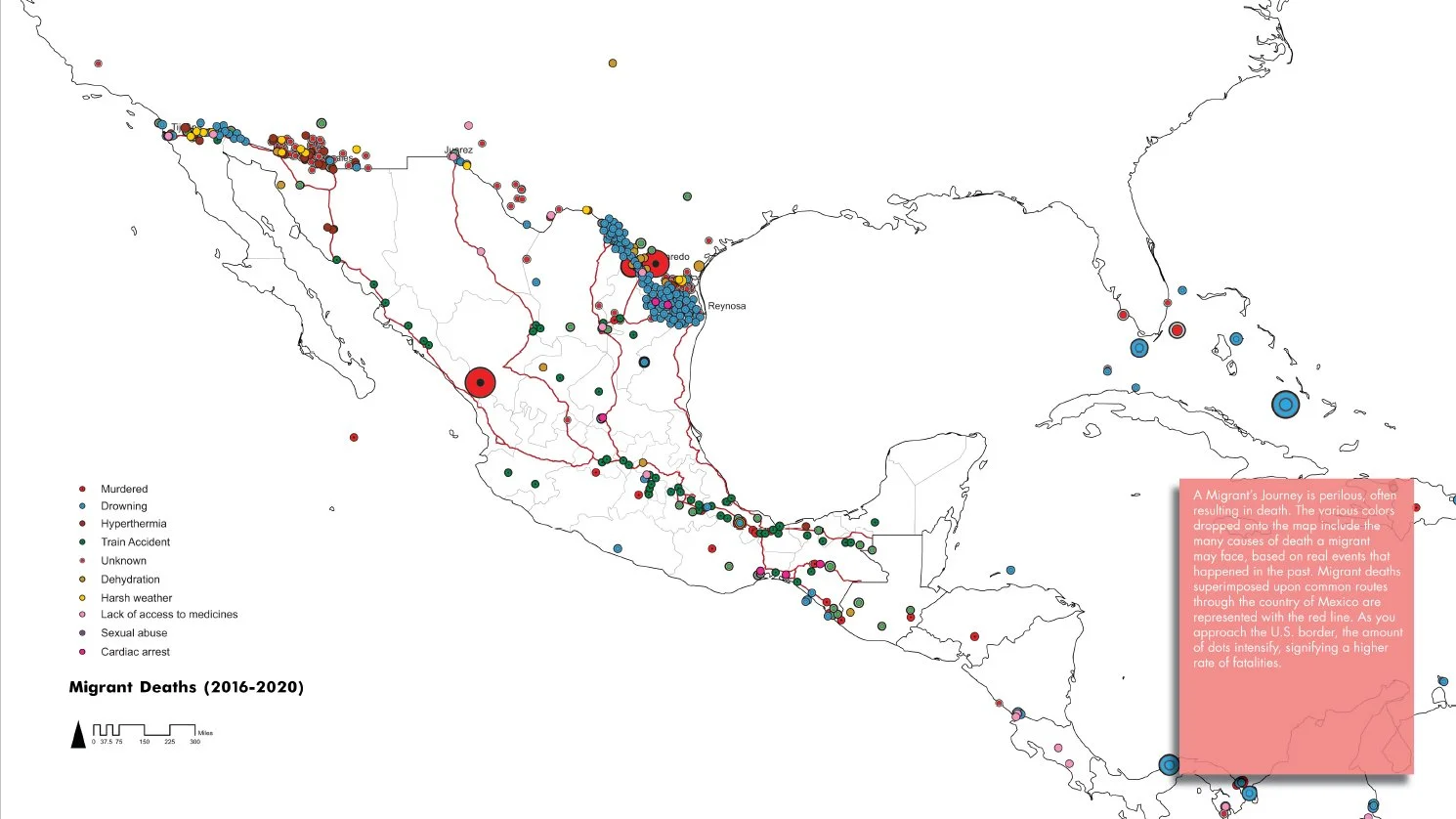

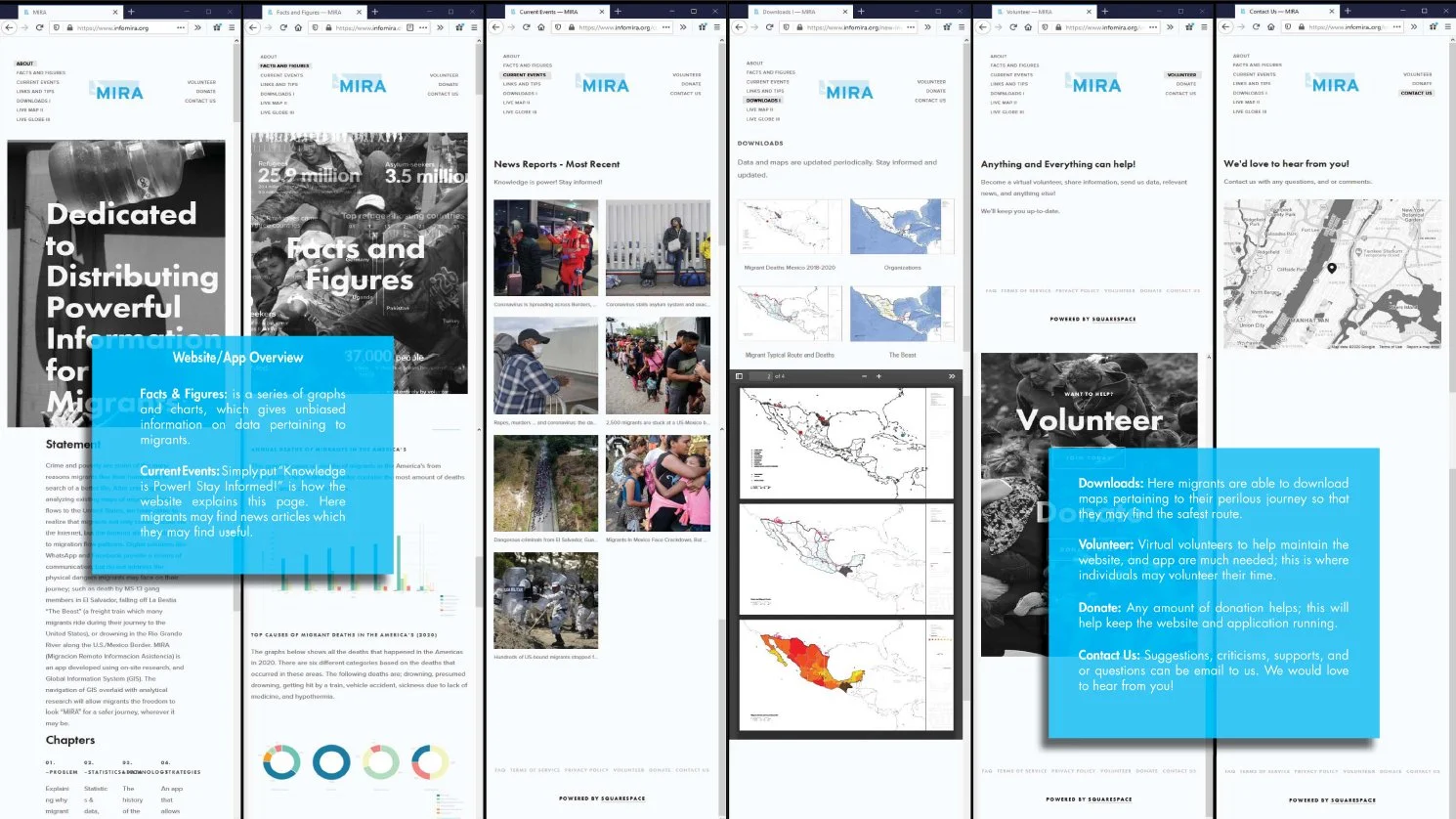

Phase 1 — Research and Mapping: Students compile datasets on routes, climate patterns, river behaviour, transport nodes, and administrative locations. GIS overlays reveal relationships between rainfall, road conditions, and checkpoint queuing. Mapping functions as analysis rather than illustration. It identifies where small architectural interventions can reduce delay or risk.

Phase 2 — Fieldwork and Interviews: Site visits to Tapachula and nearby crossings generate direct testimony from migrants, legal advocates, and municipal workers. Photography, sketching, and timed walk‑throughs record how space affects stress, privacy, and throughput. The studio documents micro‑geographies such as shade patterns, wind corridors, and the audibility of announcements.

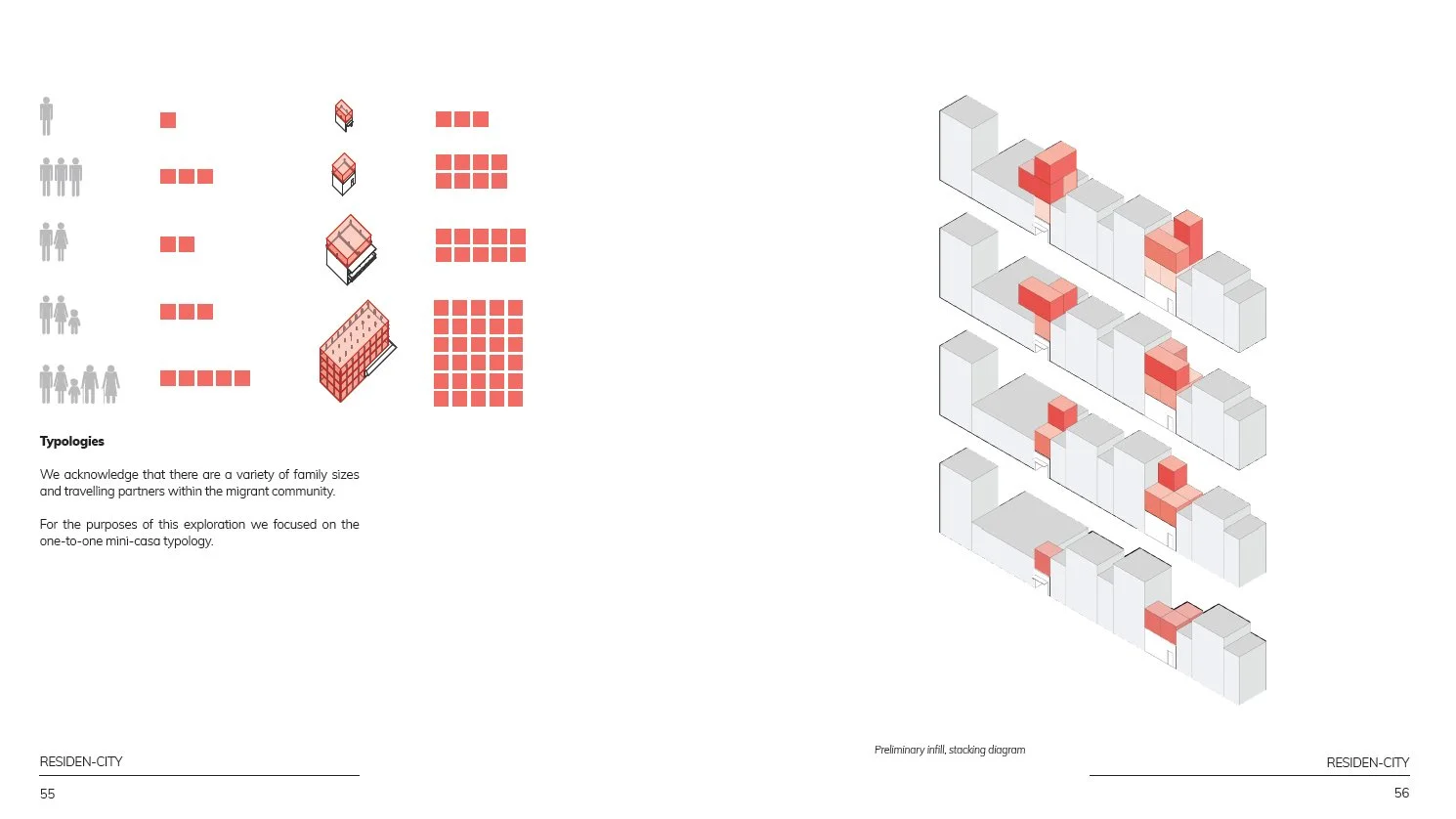

Phase 3 — Documentation and Typology: Information from the field is organised into typologies of occupation including checkpoint, shelter, clinic, courtyard, and corridor. Each type is evaluated by permanence, infrastructure, stewardship, and adaptability. The analysis recognises hybrid states: a shelter that operates as school in the morning; a plaza that becomes a triage zone after storms.

Phase 4 — Design Exploration: Teams develop modest but strategic prototypes. Examples include shaded queuing lanes that double as rainwater collectors, modular privacy partitions for interviews, portable legal clinics with integrated power and document storage, and amphibious platforms along the Suchiate that stabilise footing during floods while supporting riparian planting. Materials are selected for local availability and maintenance: bamboo, recycled steel, and micro‑concrete tiles.

Phase 5 — Synthesis and Feedback: Proposals are consolidated into a publication for partner organisations. The feedback loop between studio and field refines priorities and grounds speculation in operational needs.

Findings / Reflection

The findings reframe borders as processes rather than edges. Architecture’s task is to make these processes legible and more humane. Three observations guide this position.

First, humanitarian infrastructure depends on clarity of sequence. Many delays observed in Tapachula arise from ambiguous routing and acoustic interference. Spatial adjustments—separating intake from consultation, providing shaded staging areas, and aligning loudspeakers with waiting zones—significantly reduce stress and increase capacity. The study demonstrates that procedural clarity is an architectural effect.

Second, emergency installations can be designed for incremental permanence. Temporary tents meet immediate needs but often collapse under repeated use. The studio proposes deployable frames that accept layered upgrades: tarps to panels, panels to lattice walls, temporary benches to fixed seating with storage. This logic supports stewardship by local groups and reduces dependence on external cycles of aid.

Third, ecological repair and social care can reinforce one another. Along the Suchiate, amphibious walkways, sediment gardens, and shaded river overlooks provide safer crossings and community space while stabilising banks and improving habitat. Projects couple stormwater management with public amenity, demonstrating that resilience emerges from cooperation between hydrology and habitability.

The reflection addresses ethics and representation. Maps, photos, and drawings are not neutral; they set the terms by which people are seen. The studio adopts a protocol that privileges anonymised data, consent‑based documentation, and narratives that centre agency rather than victimhood. Architecture contributes by constructing environments where rights can be exercised without exposure.

Finally, the work argues for a pedagogy of proximity. Students learn that evidence and empathy are not opposites. Listening sessions, careful measurement, and clear diagrams become parallel forms of care. Design operates as translation, aligning institutional mandates with the everyday logic of movement and rest. In this alignment, architecture shifts from object to interface and from solution to ongoing conversation.

Credits

Architecture Filed Lab Research Program: Brittany Gray, Caitlin M McManus, Joseph Schlegel, Evelyn Terra, Henry Aguilar, Saleem Husain, Evan Mirzakandov, Nick Wu, Mimi Liebenberg, Florence Methot, Tillie O’Reilly, Samantha C Richman

Collaborators: Prof. Ali C. Höcek, Spitzer School of Architecture, International Organization for Migration (IOM), Jesuit Refugee Service, Maureen Meyer, Washington Office of Latin America (WOLA), Heber Missael Jaimes Murillo, Prof. William Brinkman-Clark, Prof. Arturo Ortiz-Struck, Sean Anderson,

Location: Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico

Year: 2019–2020

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com