Incarceration of the Future

Abstract

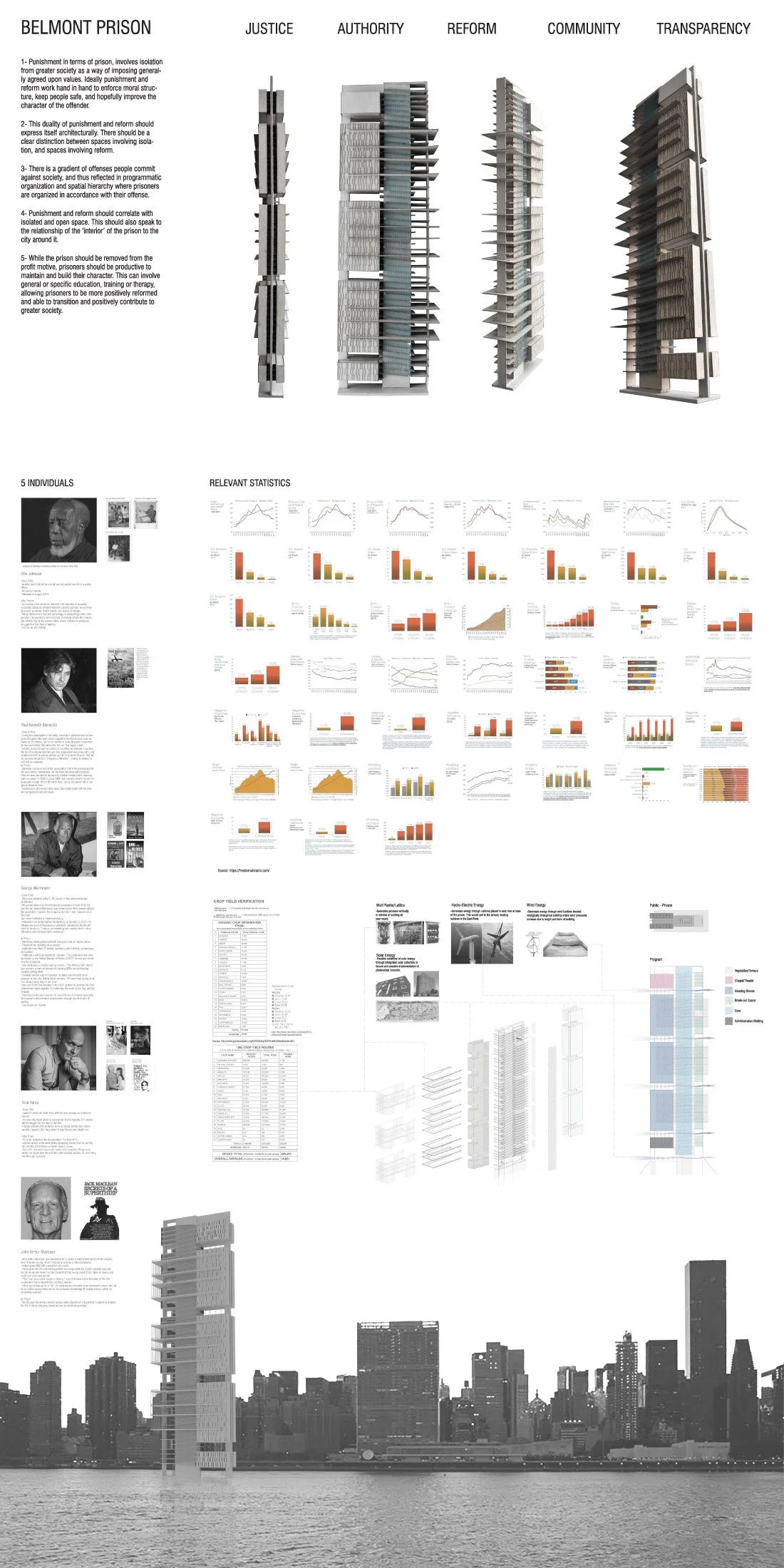

The project explores the evolving role of the prison as a spatial, ethical, and social system. Developed within the CCNY Advanced Architecture Studio, it interrogates how the architecture of incarceration—once synonymous with isolation and discipline—might instead serve as infrastructure for reintegration, education, and restorative justice. Through extensive research on contemporary correctional typologies, rehabilitation programs, and ethical design frameworks, the project argues that the future of incarceration lies not in walls, but in systems of care. Architecture becomes a mediator between governance and community, materializing the balance between accountability and empathy. The study repositions the prison as a platform for transition, learning, and healing—a civic organism embedded within its urban and ecological context rather than apart from it.

Context

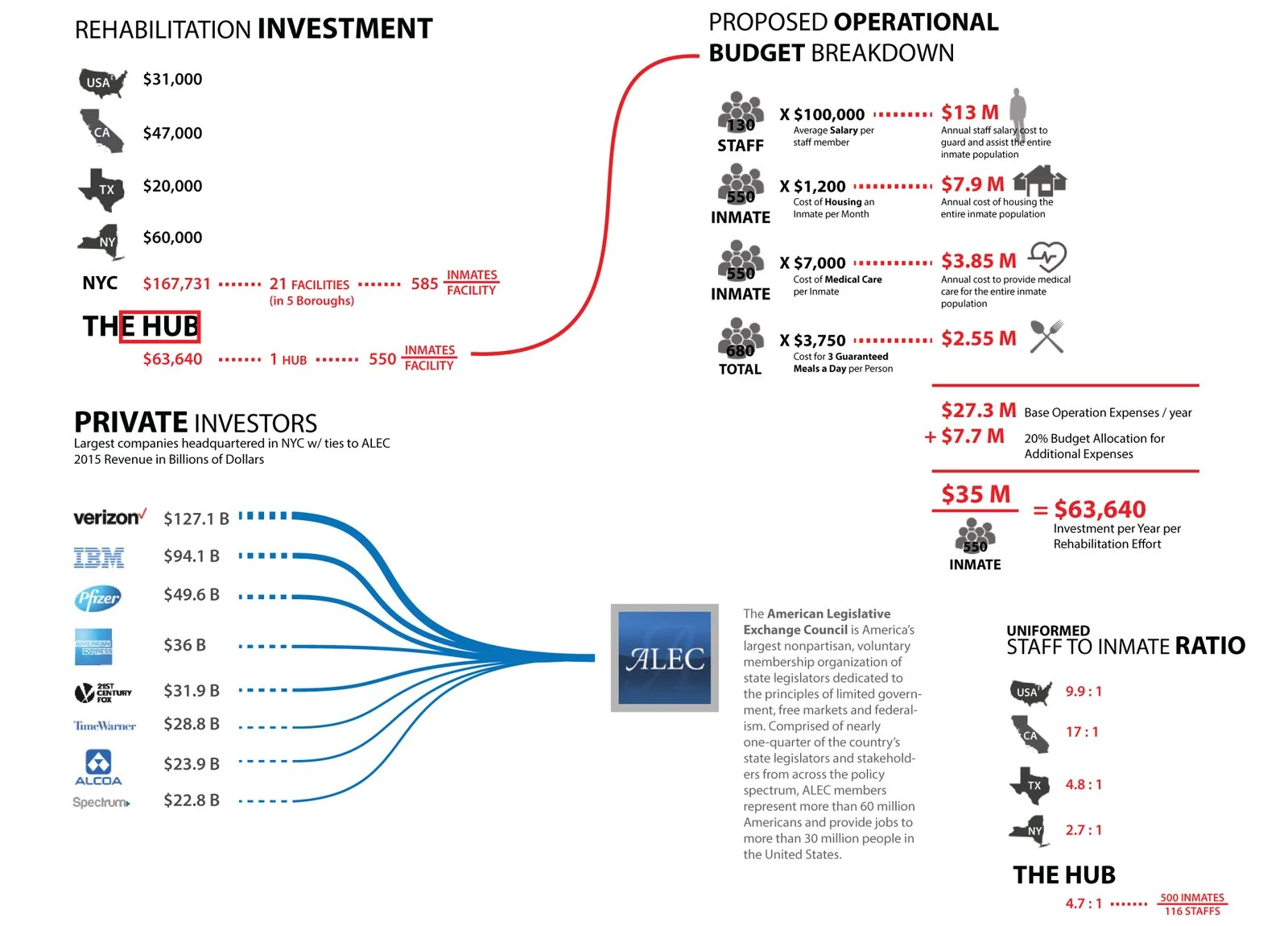

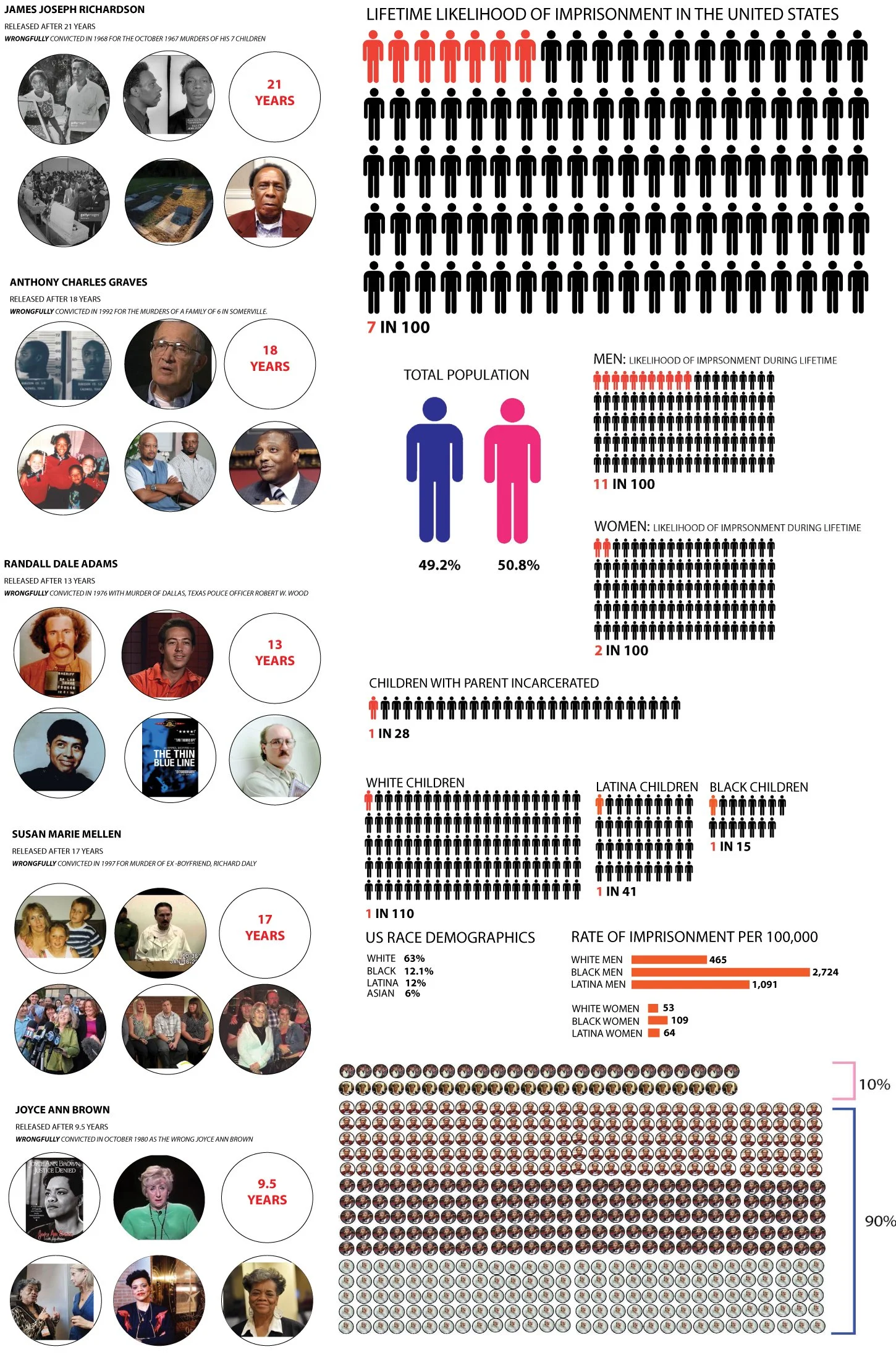

The United States holds nearly one quarter of the world’s prison population despite comprising only five percent of its inhabitants. New York State alone operates 54 facilities housing more than 50,000 inmates, alongside 35,000 parolees. This system represents not only a logistical network but also a moral and spatial framework—one that reflects societal values regarding justice, labor, and belonging.

Since 1999, the state’s inmate population has declined by nearly thirty percent, leading to the closure of thirteen correctional facilities and the elimination of over 5,500 prison beds. Yet the physical and ideological structures of incarceration remain entrenched. The typology continues to reproduce cycles of inequality through isolation, under-education, and restricted reentry pathways.

Against this backdrop, architects and planners have begun to question their professional complicity in systems that perpetuate harm. Raphael Sperry’s campaign through Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) challenged the American Institute of Architects to prohibit members from designing spaces that facilitate execution or prolonged solitary confinement—acts defined by the United Nations as human rights violations. This ethical stance reframes the role of architecture: from enforcer of confinement to advocate for dignity.

Parallel to these ethical debates, design research has examined alternative models across Europe and North America. The Danish State Prison by C.F. Møller Architects emphasizes light, openness, and normalization as instruments of rehabilitation. The Mas d’Enric Penitentiary in Tarragona, Spain, operates as a decentralized “village,” balancing security with humane environments. Projects such as PriSchool (Glen Santayana, GSD) integrate educational institutions within correctional frameworks, blurring the boundaries between campus and cell.

Incarceration of the Future situates itself within this lineage, exploring how architecture can transform from a spatial technology of control into one of collective healing. It asks: if imprisonment is inevitable in some form, can its architecture become restorative rather than retributive?

Methods

The studio’s methodology integrates comparative research, statistical analysis, and speculative design.

1. Systemic Mapping.

The research began by mapping the correctional network of New York State—its demographic patterns, facility distribution, and flows between incarceration, parole, and reentry. Data from the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS) revealed systemic disparities: overrepresentation of marginalized communities, high recidivism rates linked to educational inequity, and limited access to mental health care. These mappings reframed the prison not as an isolated object but as a node within broader social and economic systems.

2. Typological Analysis.

The team catalogued contemporary prison typologies—from high-security institutions to community-based halfway houses—and analyzed their spatial logics. Case studies included the Danish State Prison, the Rehabilitation of Palencia Prison (Spain), and speculative proposals such as the Pacific Ocean Platform Prison and Hydroelectric Waterfall Prison. Each revealed a shift from total control to layered transparency, where architecture negotiates between visibility, autonomy, and care.

3. Programmatic Research.

Using DOCCS documentation, the study examined education, health, and reentry programs within existing institutions. These ranged from vocational training (HVAC, carpentry, culinary arts) to substance-abuse and trauma recovery programs. Transitional phases such as the CASAT initiative and Federal Prisons Industries (UNICOR) provided insight into labor as both rehabilitation and exploitation.

4. Ethical Framework Construction.

Informed by Sperry’s ADPSR manifesto, the studio developed an ethical protocol for justice design—defining architectural boundaries of participation. This included a refusal to design spaces of isolation exceeding 15 days, alignment with restorative justice principles, and incorporation of community participation in design governance.

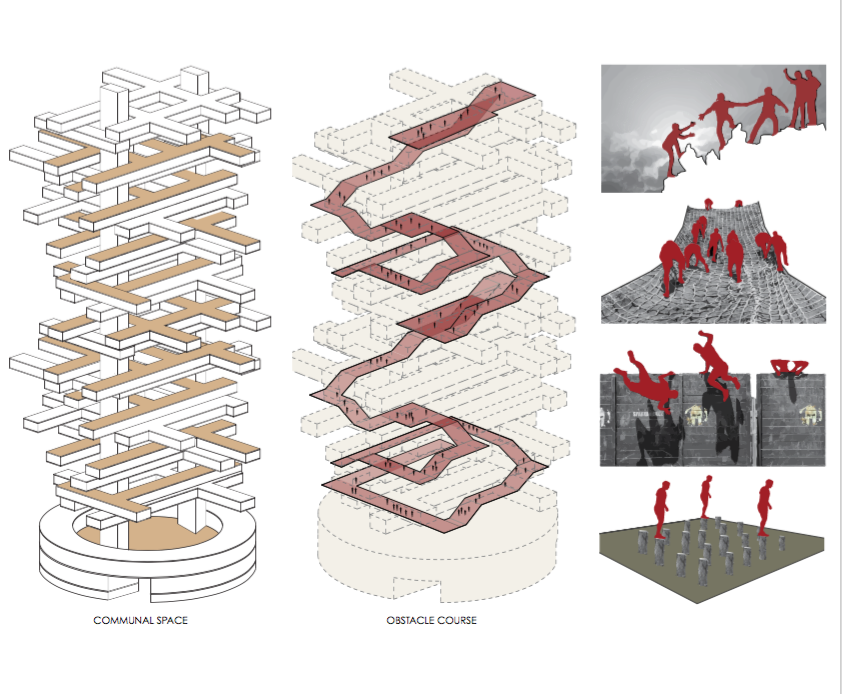

5. Speculative Prototyping.

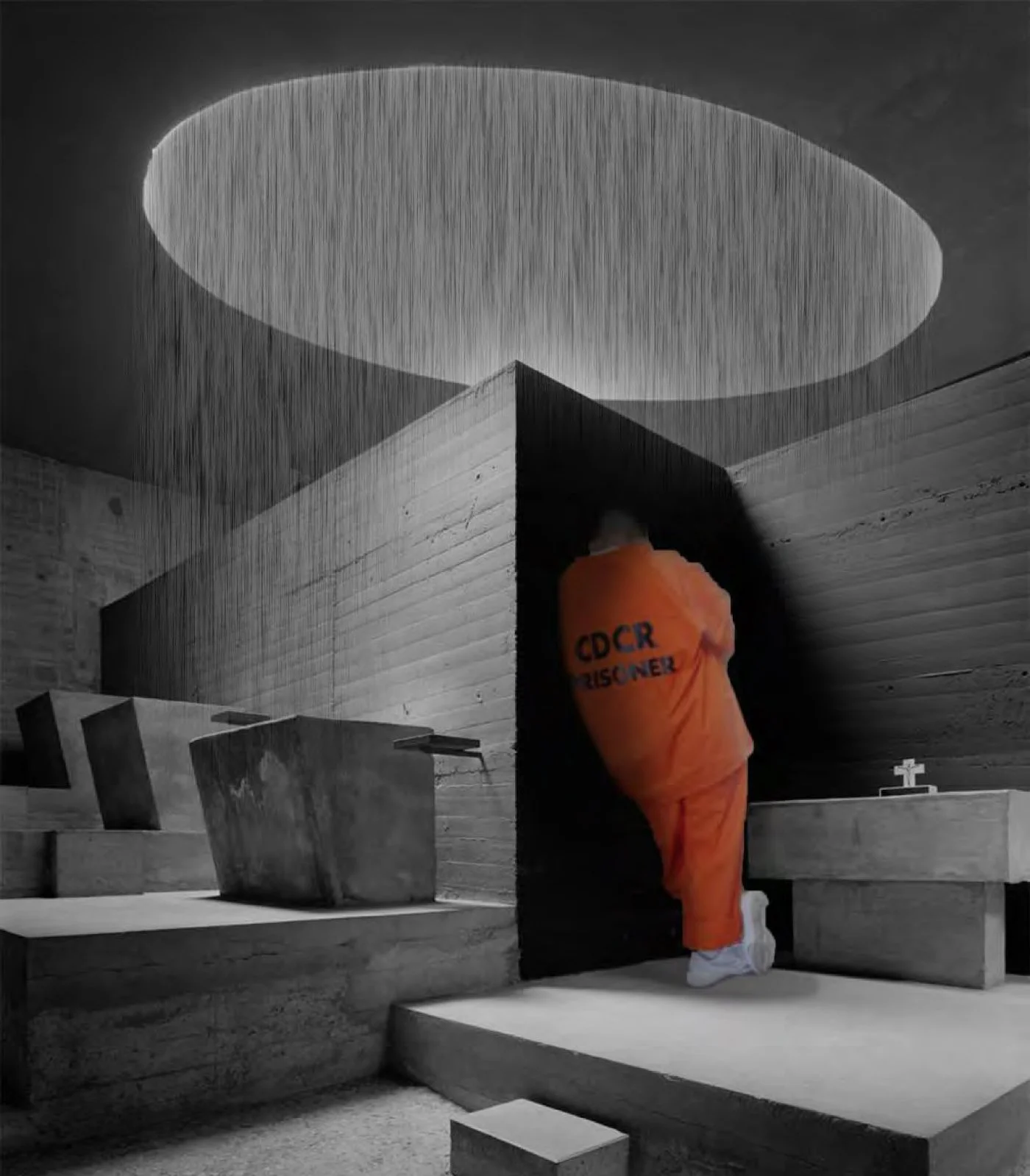

The design phase produced spatial prototypes emphasizing permeability, light, and public interface. These prototypes integrated healthcare, education, and family visitation as architectural priorities. The aim was to replace the punitive corridor-cell model with distributed environments organized around collective functions.

Findings / Reflection

1. From Isolation to Integration.

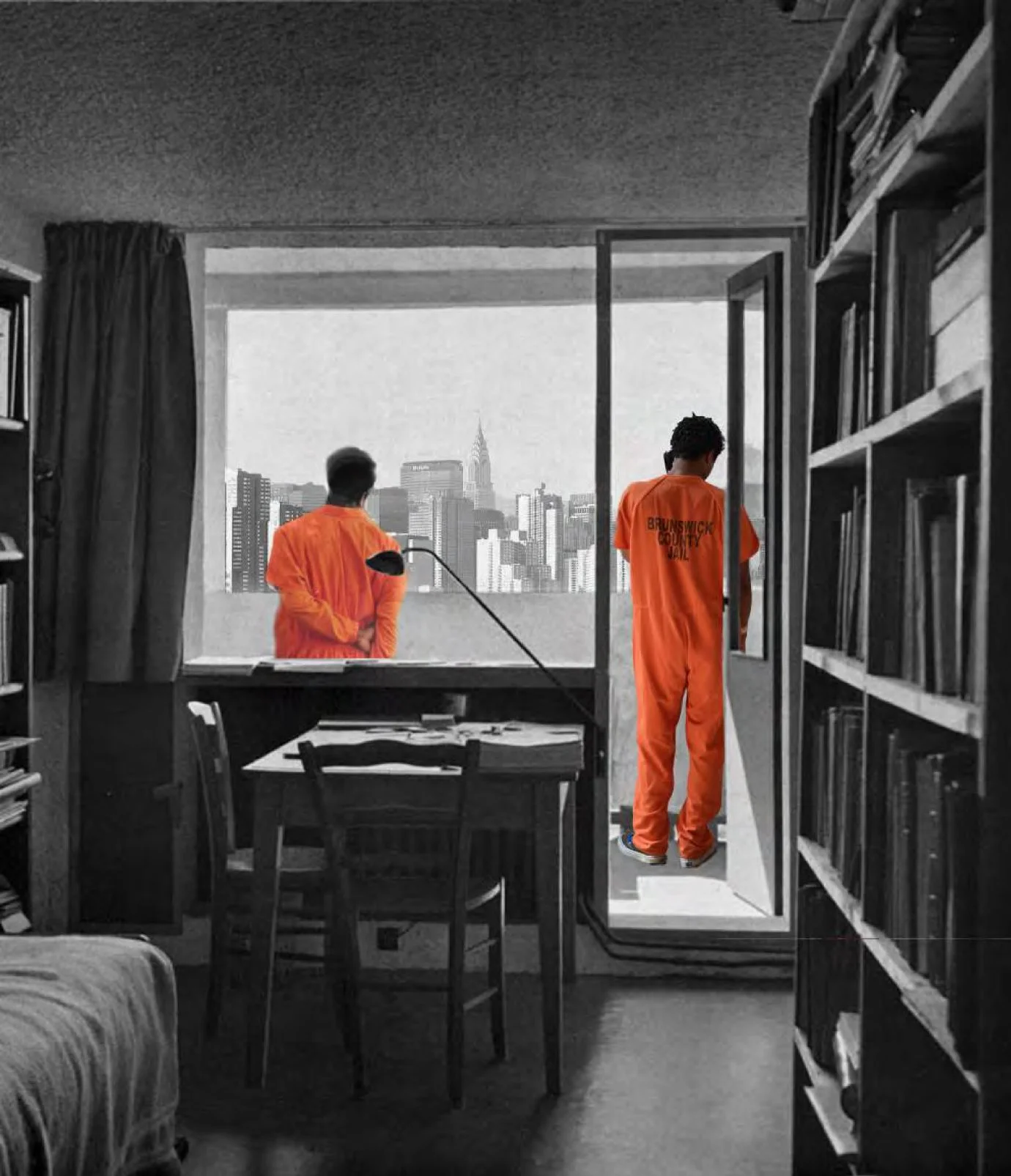

Traditional prisons externalize societal failure, displacing marginalized populations into remote compounds. The study proposes reintegration through proximity—locating future correctional facilities within urban contexts, connected to transport, education, and employment networks. The architecture thus transforms from boundary to bridge.

2. Space as Moral Instrument.

Architecture carries ethical consequence. Every wall, window, and threshold enacts a decision about visibility, agency, and power. The reimagined facility minimizes opaque segregation and maximizes spatial reciprocity—views between staff and inmates, daylight shared between cells and communal areas, and transparent circulation that fosters accountability.

3. Rehabilitation as Infrastructure.

Programs traditionally categorized as “supplementary”—education, counseling, and vocational training—are repositioned as primary spatial drivers. Classrooms, workshops, and greenhouses replace surveillance corridors as central organizing elements. Architecture becomes a support system for personal development rather than containment.

4. The Prison as Learning Ecology.

Drawing from models such as PriSchool and the Palencia conversion, the design treats the prison as a civic learning environment. Facilities host visiting educators, social workers, and community organizations. Outdoor courtyards double as gardens and classrooms, reconnecting inmates to ecological cycles and responsibility.

5. Reentry as Design Continuum.

Transitional housing and halfway programs are integrated within the same architectural framework. Rather than abrupt release, spatial gradations—ranging from secure wings to open-access pavilions—mirror psychological and social progression. This continuity reduces recidivism and reframes release as reintegration rather than rupture.

6. Ethical Architecture as Policy.

The project emphasizes that architecture alone cannot reform the justice system, but it can materialize reformative policy. Spatial design becomes a legislative instrument: transparency promotes oversight; daylight reduces aggression; spatial dignity encourages behavioral change. Architecture thus acts as governance in built form.

7. New Typologies of Care.

The proposed prototype merges elements of healthcare, education, and housing. Its core—an atrium for workshops and counseling—anchors radiating wings accommodating living, recreation, and training spaces. Security becomes environmental rather than mechanical, achieved through sightlines, trust, and participation. The facility’s materials—timber, translucent polycarbonate, and vegetated roofs—symbolize permeability and renewal.

8. Architecture of Reciprocity.

Incarceration of the Future reframes justice through reciprocity: the recognition that rehabilitation benefits both the individual and society. By replacing punishment with capacity-building, architecture contributes to social resilience. The facility operates not as an endpoint but as part of a continuous civic ecosystem linking schools, courts, and communities.

9. The Role of the Architect.

Following Sperry’s ethical argument, the architect’s responsibility is not merely formal but moral. To design prisons without addressing their social effects is to participate in systemic harm. The project proposes an expanded professional code: architects as advocates for dignity, inclusion, and transparency.

10. The Future of Confinement.

Ultimately, the project concludes that the architecture of incarceration is the architecture of society itself. Prisons mirror collective priorities—whether retribution or repair. Incarceration of the Future envisions a shift toward architectures of mutual responsibility: facilities that dissolve into civic networks, enabling individuals to rejoin rather than remain excluded from the collective body.

Credits

Architecture Field Lab Research Program: Yoosef Abdul-Emir, Shu Ting Lin, Michail Pikes, David Tovar, Eunice Jung, Rolando Solorzano, Brett Barshay, Jun Nam, Suzan Kallash, Fanhor Sanchez Patino, Nicole Montenegro, Nadia Habib, Rodrigo de Dios Mulet, Yaakov Blum

Collaborators: CCNY Advanced Studio, Peter Krasnow FAIA, Prof. Judy Ryder

Location: New York State (Research scope), global case studies (Spain, Denmark, Iceland)

Year: 2017–2018

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com