Panama — Remote Clinic

Abstract

The project examines the intersection of architecture, medicine, and logistics in tropical and resource-limited contexts. Conducted in the Graduate CCNY design studio led by Martin Stigsgaard and Ali C. Höcek, it focuses on mobile and semi-permanent clinics developed for remote regions of Panama. Working with the Northeast chapter of Volunteer Optometric Services to Humanity (VOSH) and the El Dorado Rotary Club, the research investigates how short-term humanitarian operations can evolve into long-term frameworks of care. The project reframes the temporary clinic as a civic instrument—an adaptable system that aligns climate, logistics, and community participation. Through mapping, observation, and prototyping, it explores how design can convert urgency into continuity and transform acts of aid into acts of reciprocity. Architecture becomes a coordinating medium, linking the ethics of care with spatial intelligence.

Context

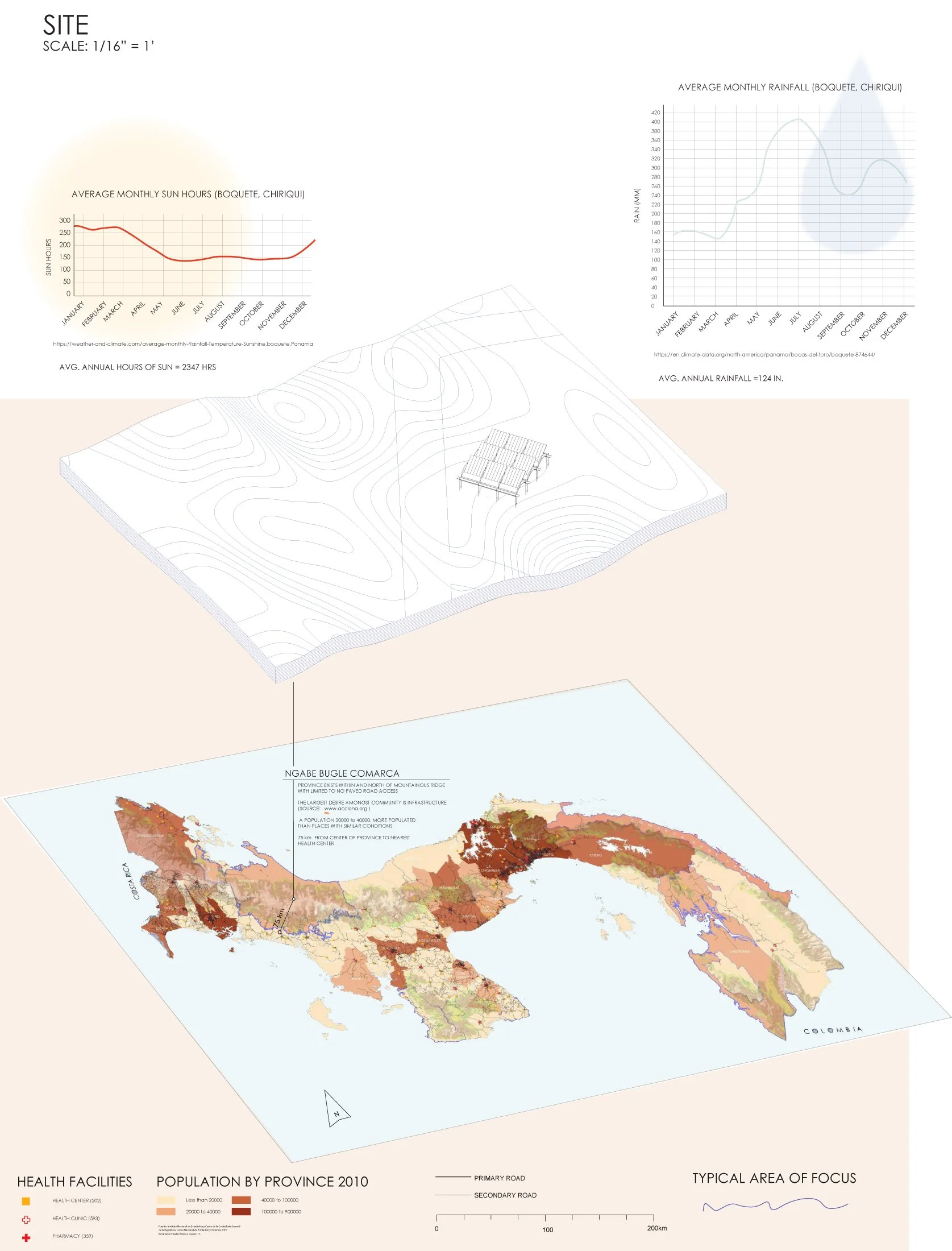

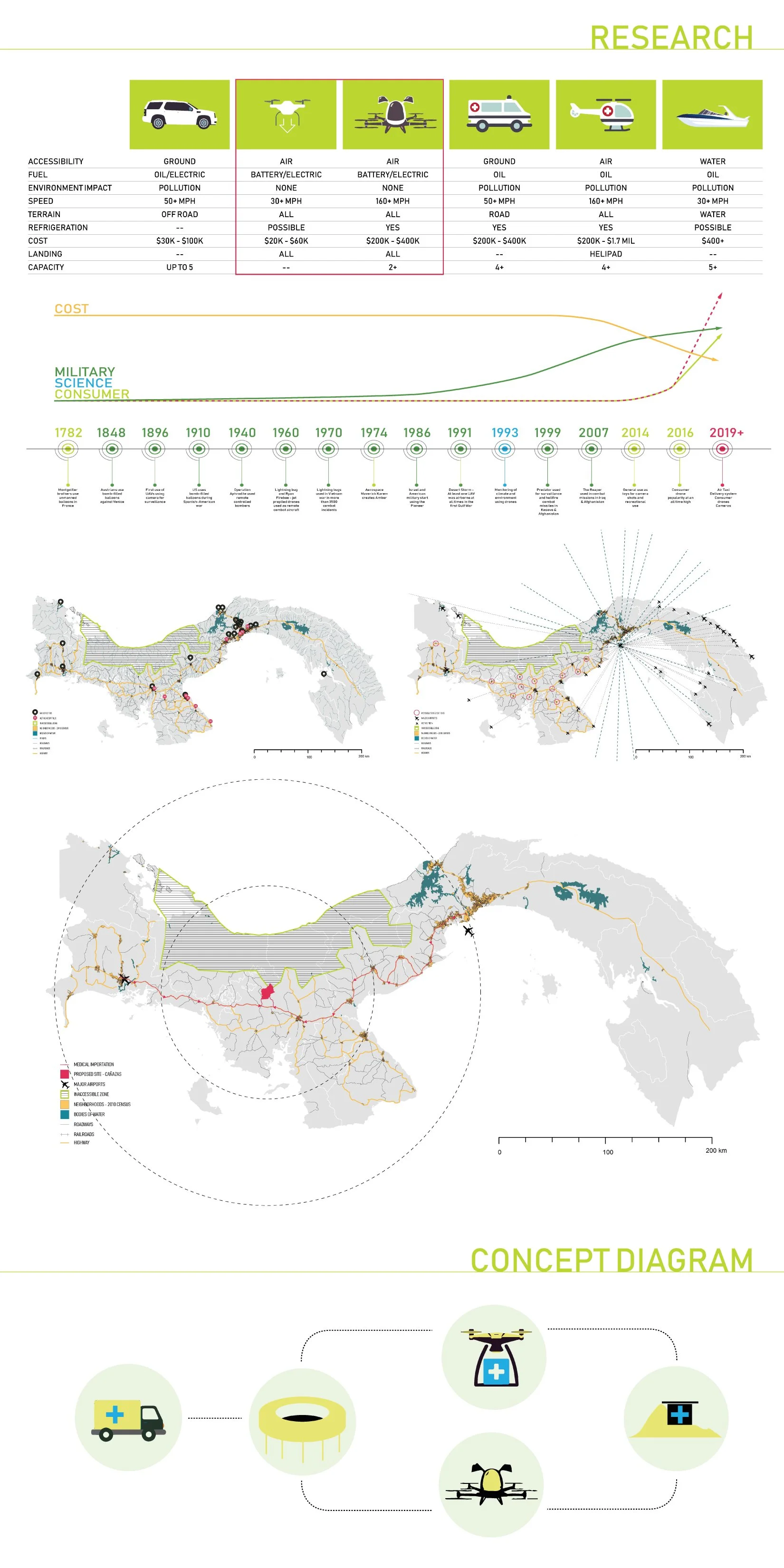

Panama’s geography defines its healthcare challenges. A narrow corridor between two oceans, the country’s mountain ranges and tropical climate produce stark differences between urban and rural conditions. While Panama City and Colón have advanced hospitals and logistics hubs, indigenous and agricultural regions face limited medical access. Road connectivity drops sharply outside major provinces; heavy rain, heat, and seasonal flooding often isolate villages. Within this geography, short-term volunteer missions play a crucial role in delivering care where the national system cannot maintain permanent presence.

Each year, teams of doctors, optometrists, and students travel from North America to Panama to conduct intensive four-to-five-day clinics. Operating in borrowed schools or community halls, they transform classrooms into diagnostic zones and corridors into waiting rooms. A single mission can treat over three thousand patients, many receiving medical attention for the first time. Yet the system remains fragile. It depends on temporary structures, improvised circulation, and environmental tolerance. Heat, glare, and humidity affect both staff and patients, while limited privacy and acoustic stress complicate sensitive consultations.

The studio situates its inquiry within this logistical ecology. The question it poses is not how to replace volunteer work but how to amplify its legacy. What spatial frameworks could allow these missions to evolve into a distributed network of local resilience? The field study in the Penonomé region provided first-hand data on patient flow, volunteer routines, and environmental performance. Observations included long queues under the sun, overlapping departmental noise, and inconsistent signage. These patterns, mapped and timed, formed the basis for a new spatial intelligence of care. The project recognises that every logistical challenge has architectural consequences—and that every architectural adjustment can improve the ethics of service.

Methods

The methodology integrates mapping, observation, systems design, and prototyping. It proceeds in four linked phases.

Phase 1 — Observation and Measurement: Students documented patient journeys through diagrams and timestamps. Data revealed that nearly half of the waiting time occurred outdoors without shade or airflow. Temperature and humidity sensors tracked the climatic gradient across the site, identifying hot zones and cross-ventilation paths. These findings provided empirical grounding for design intervention.

Phase 2 — Systems Analysis: The team reconstructed clinic operations as a flowchart of interactions—intake, screening, diagnostics, consultation, pharmacy, and exit. Instead of organising departments by profession, the studio proposed a sequence-driven plan structured around patient experience. Parallel research into Panama’s construction practices mapped local material supply chains, revealing opportunities for low-cost prefabrication and repair.

Phase 3 — Design Prototyping: Each student developed modular components optimised for rapid assembly and climatic performance. Examples include demountable bamboo canopies with reflective membranes, collapsible furniture that converts into classroom desks, and solar-powered light panels integrated into canopy ribs. Designs were tested for weight, airflow, acoustic absorption, and ease of cleaning. Field simulations measured how new layouts improved visibility and reduced congestion.

Phase 4 — Manual and Implementation: The results were compiled into a bilingual manual for NGOs and local authorities. It includes plan templates, component catalogues, and environmental guidelines, allowing each mission to build on previous iterations rather than improvising anew. The manual formalises design as a transferable protocol of care.

Findings / Reflection

The study concludes that healthcare infrastructure in tropical contexts must be conceived as choreography rather than composition. Efficiency, comfort, and trust depend on the order and clarity of movement. Three interrelated findings define this position.

Finding 1 — Climate as Active Design: The clinic is both shelter and instrument. Shade, wind, and water regulation are integral to care. Roof geometry, height, and orientation directly influence temperature and workflow. Prototypes integrating vented ridges and high canopies reduced interior heat by up to six degrees Celsius. Rainwater gutters and evaporative cooling devices supported hygiene and comfort. The design treats environment not as obstacle but as collaborator.

Finding 2 — Care as Coordination: The research redefines care as an act of coordination among volunteers, patients, translators, and logistics teams. Architecture structures this coordination by clarifying routes, sequencing encounters, and distributing light and sound. Movable partitions create zones of privacy without severing connection. Shared tables, labelled storage, and colour-coded signage turn organisation into empathy. Design acts as a protocol for fairness.

Finding 3 — Reciprocity as Continuity: The long-term legacy of humanitarian work depends on reciprocity. The studio promotes 'borrowable infrastructure'—elements designed for dual use beyond the mission. Benches become classroom furniture; canopy frames serve as market shelters; storage crates transform into public seating. This adaptability embeds continuity within temporality, transforming one-off aid into shared resource. Architecture thereby becomes a medium of exchange between guests and hosts.

The reflection extends beyond logistics. It addresses ethics, pedagogy, and resilience. The project resists the image of humanitarian heroism, which often masks systemic inequality. Instead, it cultivates a practice of situated agency, where design emerges through listening and iteration. The collaboration with medical volunteers highlights parallels between diagnosis and design: both rely on observation, sequencing, and care for context. Each drawing becomes a prescription for balance.

Climate change further situates the study within global urgency. Rising temperatures and unpredictable storms increase disease and disrupt logistics. The mobile clinic becomes a micro-infrastructure of adaptation—able to relocate, reassemble, and restore connectivity after crisis. Its modularity is not a style but an ethic. The prototypes illustrate how local materials and knowledge can reduce dependency on global supply chains, strengthening autonomy.

Pedagogically, the studio demonstrates a model of reciprocal learning. Students operate as field researchers, designers, and participants, translating observation into action. Their collaboration mirrors the system they study—distributed, adaptive, and interdependent. The approach affirms that precision and empathy are not opposites but complementary dimensions of responsible practice.

Ultimately, the findings reframe humanitarian architecture as an ongoing civic infrastructure. When short-term missions embed capacity for maintenance and reuse, they extend the reach of national healthcare systems. Design becomes a form of continuity—an architectural promise that care, once delivered, does not disappear with departure.

Credits

Architecture Field Lab Research Program: Kari Kleinmann, Pauline Dang, Valmira Gashi, Julia Sokolova, Tom Piscina, Ignacio Lopez Droguett, Alexandra Checa, Alexandra Chepanova, Dovber Blasberg, Jared Passen, Tiana Howell, Arezoo Issapour

Collaborators: Prof. Ali C. Höcek, NeVosh (Volunteer Optometric Services to Humanity), El Dorado Rotary Club of Panama, University of Panama, Dr. Inna Rozentsvit, Dr. Rocco Robilotto (Optometry) (VOSH), Prof. Hillary Brown, Prof. Monica Bertolino, Prof. Are Risto Øyasæter, Tahir Demircioglu

Location: Penonomé Region, Panama

Year: 2019–2020

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com