ParallaX Shift: Under Siege

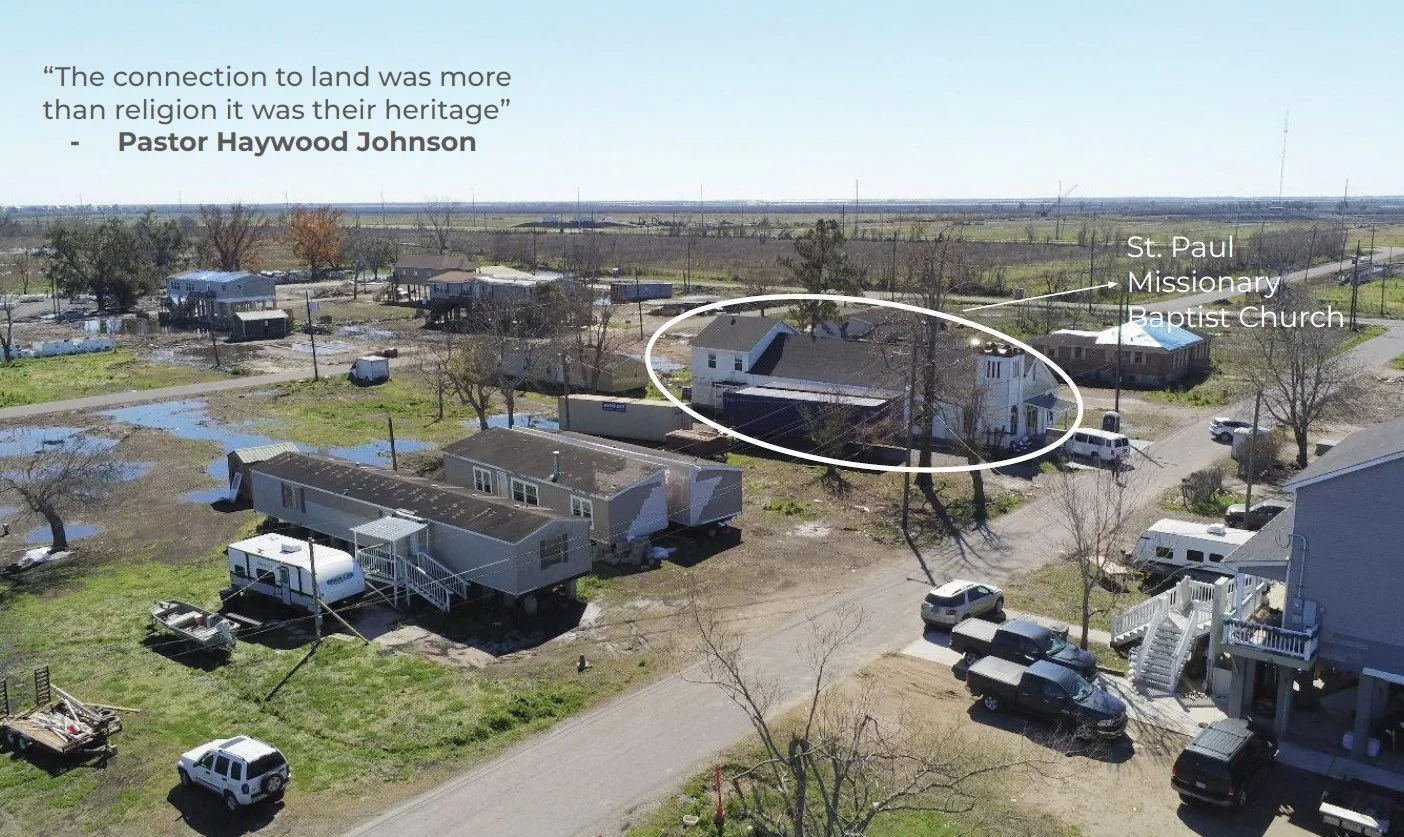

Site visit to Grand Isle, Louisiana after Hurricane Ida 2021

Abstract

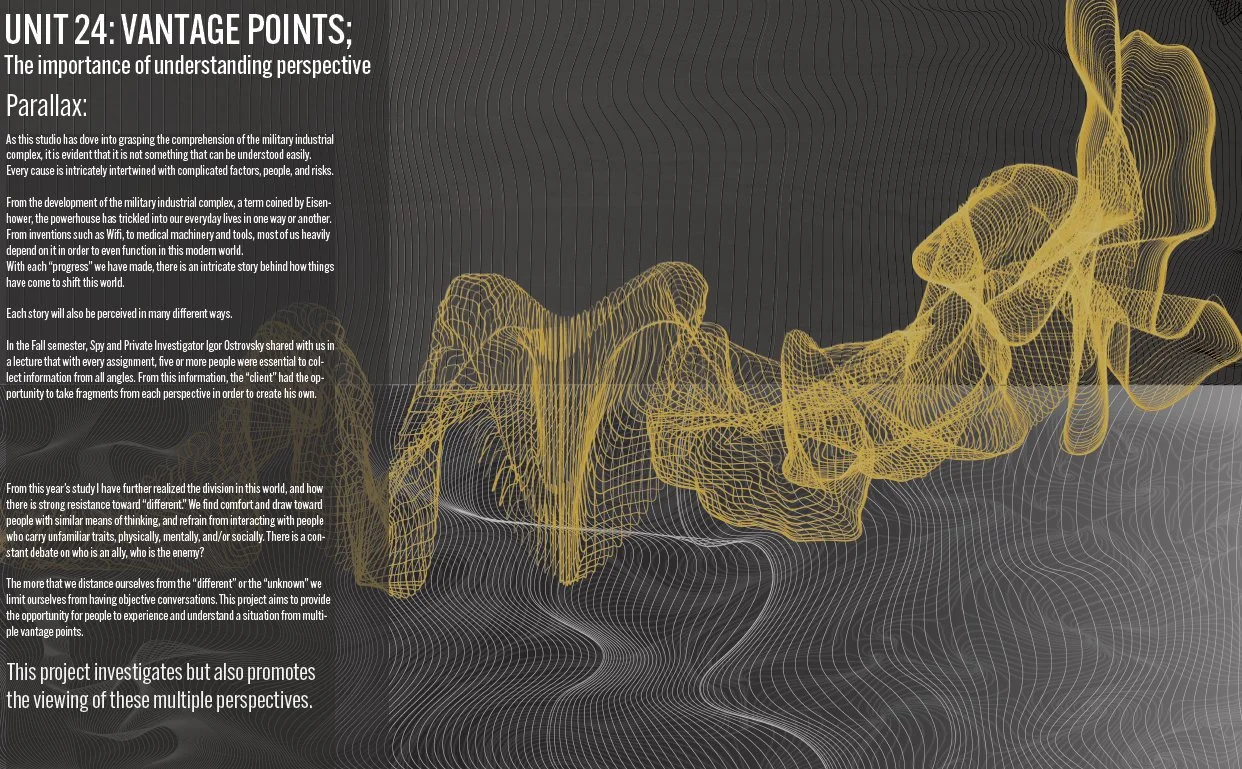

ParallaX Shift explores perspective as both a perceptual mechanism and a cultural construct. Developed within Studio STIGSGAARD’s Parallax: Under Siege framework, the project studies how architecture can expose the multiplicity of truths embedded in sites of memory, conflict, and identity. Using Louisiana as its testing ground—a region of abundance shadowed by structural poverty—the work investigates how architecture can reconcile contradictory readings of progress, history, and belonging. Drawing from Steven Holl’s writings on parallax and embodied perception, the project proposes a typology that translates the tension between perspectives into spatial form. The design becomes a medium for dialogue: a framework through which visitors inhabit multiple vantage points simultaneously, questioning inherited narratives and recognizing interdependence between bodies, histories, and systems.

Context

The studio begins from the recognition that perception is never neutral. Parallax—the apparent displacement of an object when viewed from different positions—becomes an epistemological and ethical metaphor. In architecture, it manifests as the coexistence of divergent truths within the same space. The project situates this inquiry within the complex social and ecological context of southern Louisiana, where environmental extraction, industrial power, and cultural memory intersect.

Off shore Oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico

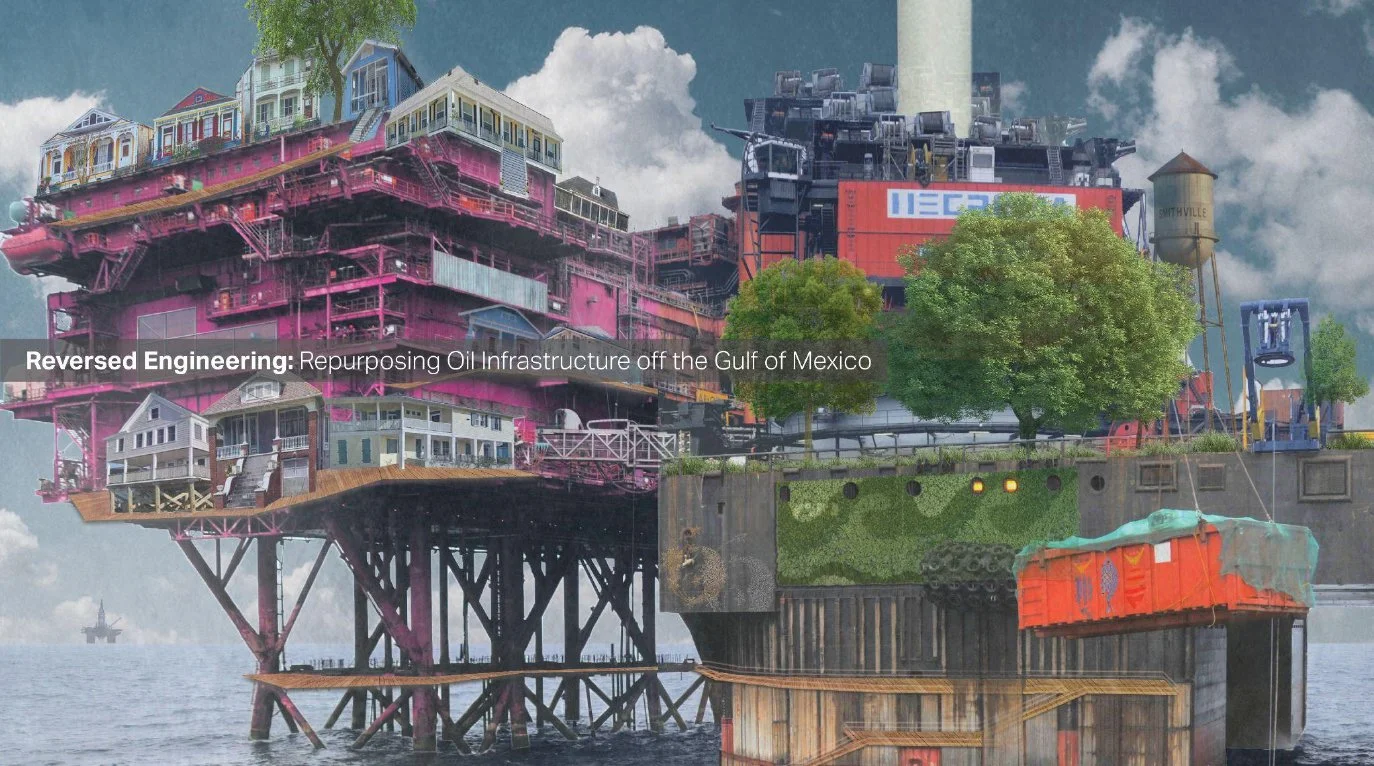

Louisiana presents a paradox: it ranks among the nation’s top producers of oil, gas, and sugar, yet also among the lowest in health, education, and income equality. The same infrastructures that generate economic wealth perpetuate vulnerability. The contradiction mirrors the larger “military–industrial complex,” whose innovations—GPS, internet, medical imaging—emerge from systems of control and conflict. The studio therefore asks: how might architecture redirect such forces toward empathy, reciprocity, and civic meaning?

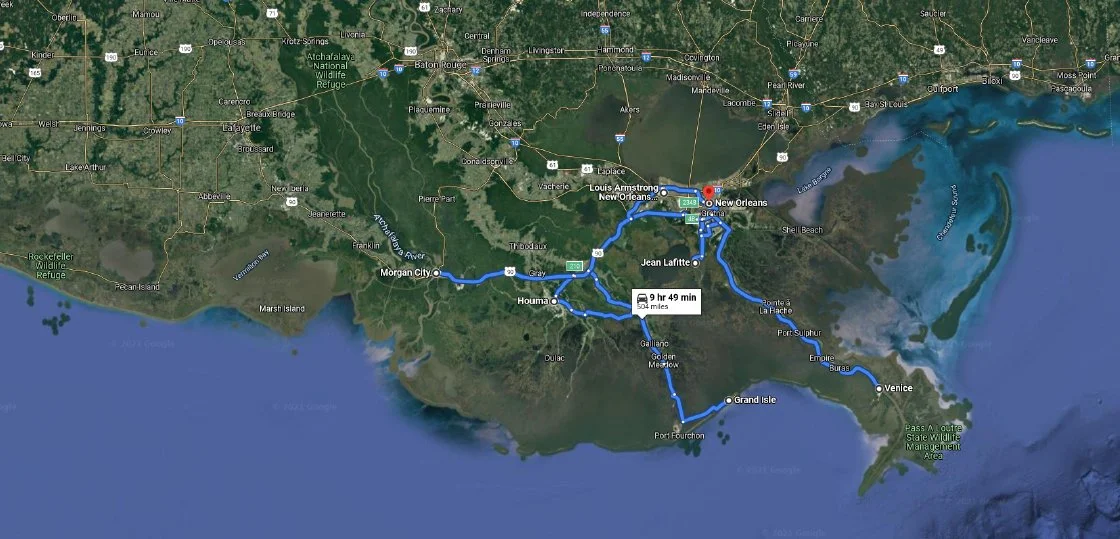

The investigation engages two parallel trajectories. One is perceptual—the relation between body, space, and narrative; the other systemic—the entanglement between industry, ecology, and governance. The project’s research trip through Louisiana traced these relations in situ: petrochemical corridors, flooded parishes, and cultural institutions such as the National WWII Museum. Students observed how built form often stabilizes singular viewpoints—heroic, national, or corporate—while excluding alternative experiences. The museum’s narrative, for instance, privileges the American soldier’s perspective while erasing those of civilians, allies, or adversaries.

For project author Mayu Uchiyama, the tension was personal. As a Japanese woman educated in the United States, she navigates dual historical narratives—those of Hiroshima and Pearl Harbor. This embodied parallax—seeing the same event from two moral coordinates—became the conceptual ground for the design. Architecture becomes a site of negotiation, not resolution; it constructs frameworks that allow opposing truths to coexist and be perceived in relation rather than isolation.

Methods

The project employs a hybrid methodology combining field research, phenomenological analysis, and spatial simulation.

1. Perceptual Mapping.

The process begins with diagramming perception itself. Using techniques derived from Steven Holl’s Parallax, the project maps how spatial experience unfolds through bodily movement, duration, and orientation. The human figure becomes a sensor that measures shifts in perspective, light, and distance. This mapping is both visual and temporal—a record of how space reveals itself over time.

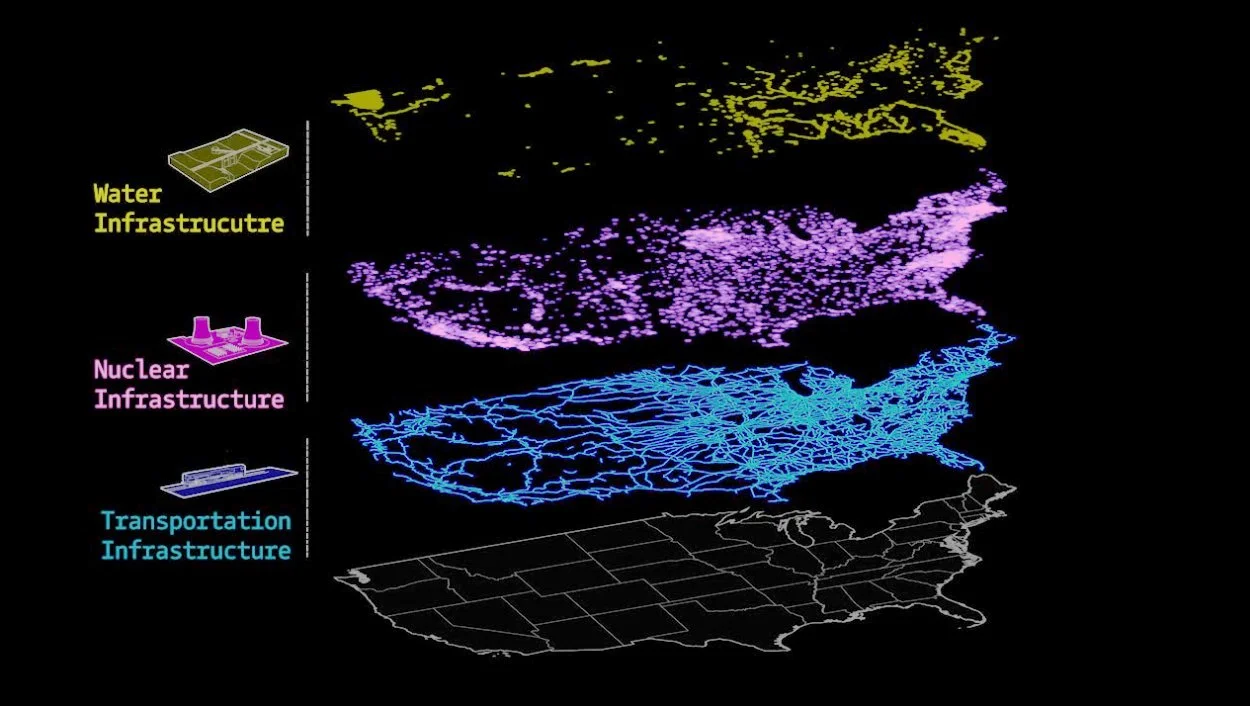

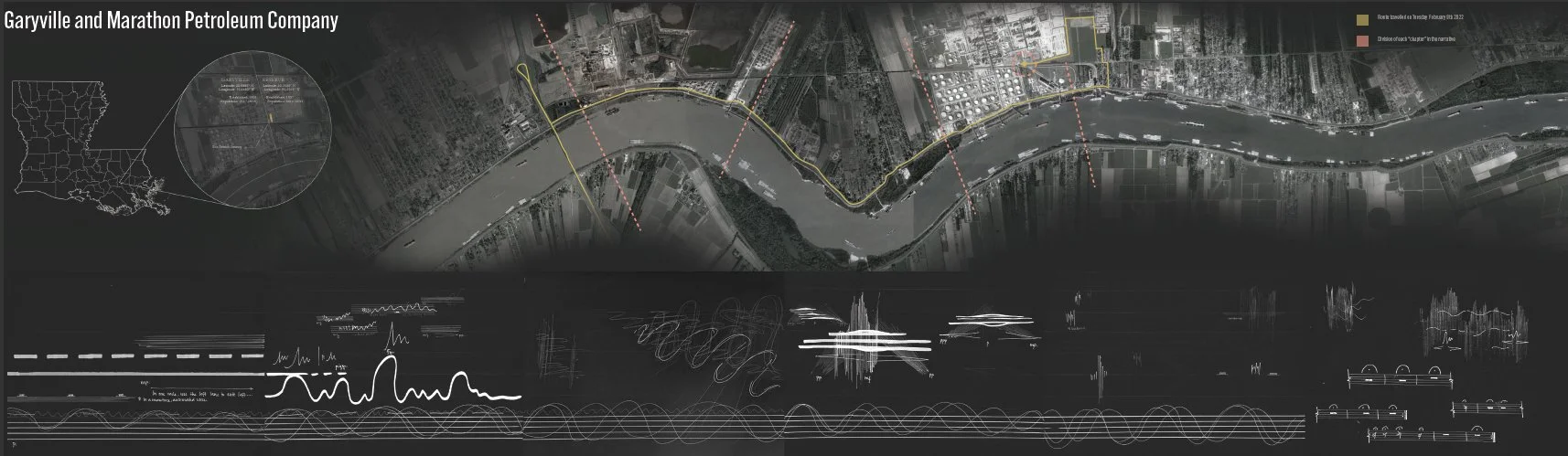

2. Systemic Cartography.

Parallel to this perceptual study, the research constructs layered maps of Louisiana’s industrial and social systems: pipelines, flood zones, migration paths, and socioeconomic indices. These maps expose systemic asymmetry—the coexistence of resource abundance and social deprivation. By overlaying physical and political geographies, the method reveals how perception and policy co-produce territory.

3. Narrative Collage.

Drawing from interviews, museum analysis, and personal testimony, the project assembles a mosaic of perspectives around war, migration, and identity. These narratives are translated into spatial sequences—each representing a distinct viewpoint. The act of collage resists synthesis; instead, it allows friction between fragments to generate meaning.

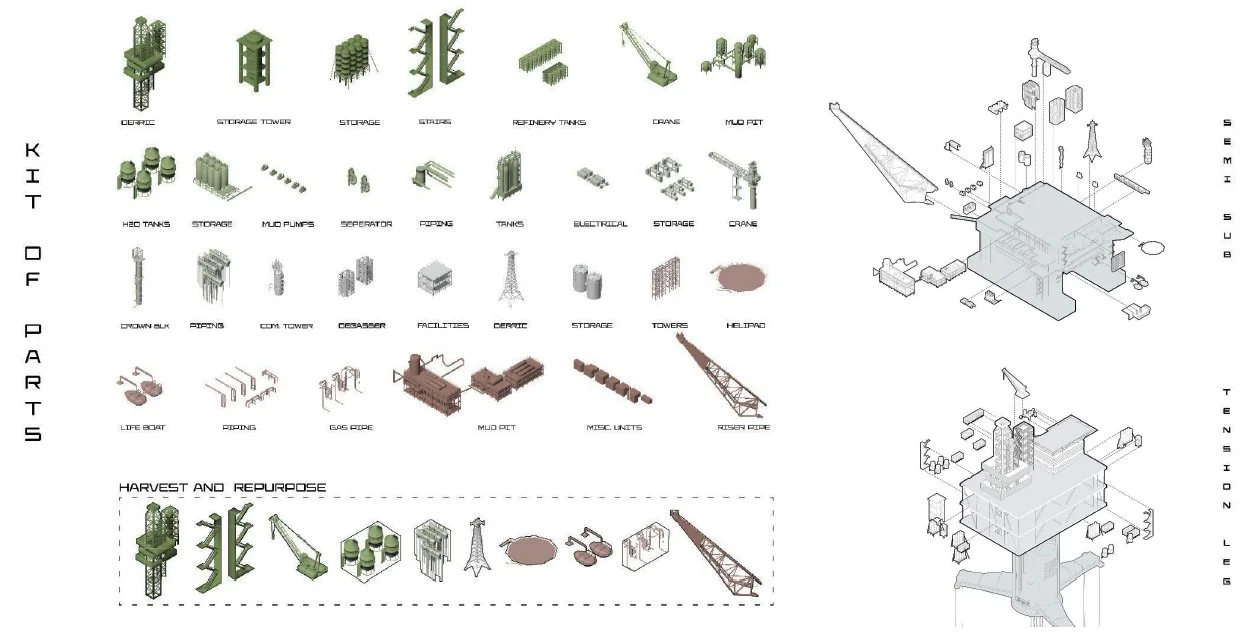

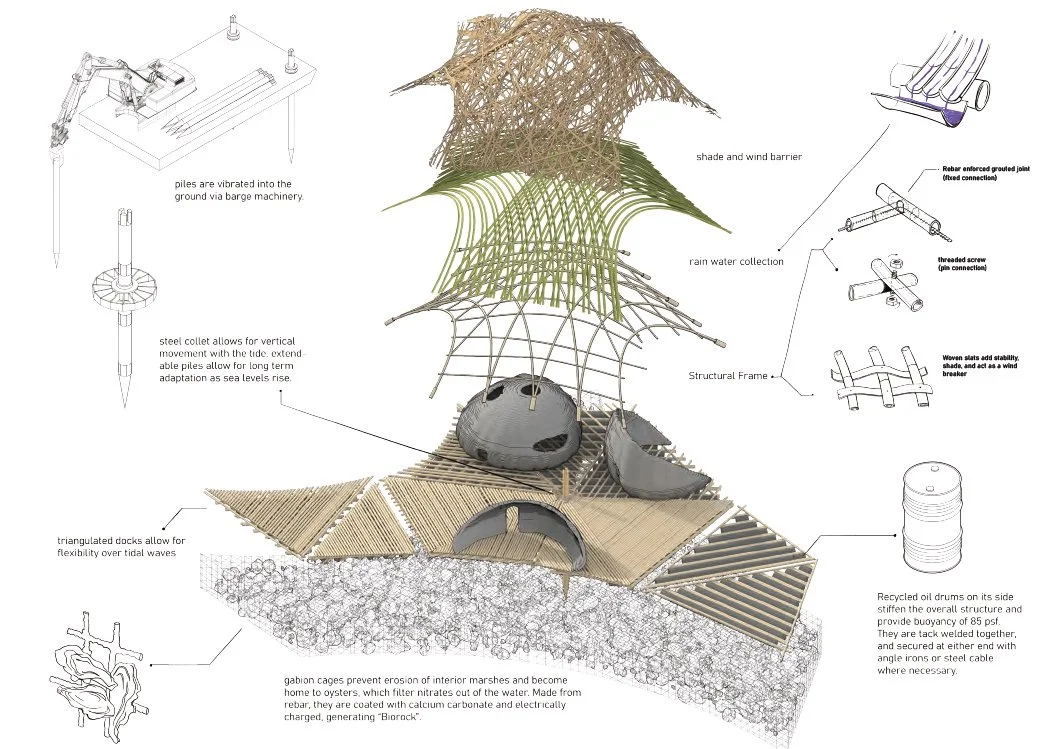

4. Architectural Prototyping.

Using physical models and digital simulation, the studio tests how architecture can spatialize multiple viewpoints without hierarchy. Plans and sections are conceived as shifting alignments rather than fixed compositions. Spaces unfold through rotation, reflection, and inversion—mirroring the perceptual logic of parallax. Material studies explore transparency, reflection, and acoustic layering as mediums of coexistence.

5. Ethical Calibration.

Each design iteration is evaluated not for formal beauty but for ethical legibility: does it allow conflicting truths to be visible? does it produce empathy through perception? This calibration frames design as a moral as well as spatial act.

Findings / Reflection

1. Perception as Politics.

Architecture is not neutral; it conditions what can be seen and from where. By staging multiple vantage points, the project transforms perception into a tool of critique. The resulting building—part archive, part observatory—exposes the constructed nature of historical truth. Visitors encounter spatial contradictions: corridors that double back, mirrored surfaces that distort, platforms that align only momentarily. Each spatial decision translates an ethical one—the acceptance of plurality over singularity.

2. Body as Instrument.

Spatial experience is re-centered on the moving body. As users traverse ramps, bridges, and viewing platforms, they become aware of their own positionality. The building choreographs shifts in balance, scale, and orientation to materialize the instability of perspective. This performative structure converts cognitive parallax into physical empathy: by feeling disorientation, one recognizes the limitations of one’s viewpoint.

3. Architecture as Narrative Framework.

Rather than prescribing content, the design provides a narrative infrastructure—a system of frames, apertures, and sequences through which multiple stories can be told. Exhibits, projections, and soundscapes occupy this open framework. The architecture thus acts less as a monument than as a mutable stage for storytelling, adaptable to future interpretations.

4. Conflict as Constructive Medium.

The research reveals that contradiction itself can be generative. By juxtaposing industrial Louisiana’s extractive landscapes with the personal narrative of wartime memory, the project exposes parallels between ecological and cultural exploitation. The design embraces this discomfort: its overlapping structures echo the pipelines and levees that dissect the region, yet reprogram them for connection and dialogue.

5. Material Parallax.

Material experimentation extends the conceptual logic into the tectonic realm. Alternating layers of glass, metal mesh, and concrete form gradients of opacity that respond to light and movement. Sound-reflective and absorptive surfaces create acoustic parallax, where multiple sonic environments coexist. These manipulations transform perception into an active process—one must move, listen, and adjust to understand.

6. Educational Agency.

The project evolves into a pedagogical model. By allowing users to reconstruct their own version of events, it teaches critical perception. In contrast to traditional museum design, which delivers linear narrative, ParallaX Shift proposes a networked epistemology where truth emerges from relation. This model could extend to civic education, media literacy, and participatory planning, offering architecture as a framework for collective understanding.

7. Parallax as Ethical Practice.

At its core, the work asserts that architecture’s ethical potential lies in framing—not solving—conflict. The capacity to hold multiple truths, to host difference without erasure, becomes an act of care. ParallaX Shift demonstrates that perspective is not merely visual but relational: to see differently is to coexist. The project concludes with an open proposition—an architecture that does not dictate meaning but choreographs the conditions under which meaning can evolve.

Field Trip Map

Credits

Architecture Field Lab Research Program: Harry Teitelman, Poorvi Gupta, Katrina Knudsen, Reid Kamhi, Cristian Calle, Coleman Downing, Hito Rodriguez, Matthew Hanson, Mayu Uchiyama, Danielle Rabinowitz (UNIT 24 2021-22)

Collaborators: Spitzer School of Architecture, Prof. Demir Purisic, Prof. Dominick Pilla, Prof. Jamie Edindjiklian, Prof. William Brinkman_Clark, Fabiola Menchelli (Artist), Ryan Faith (National Defense and Space Exploration Expert), Neil Herman (Retired FBI Agent & Former Head of Joint Terrorism Task Force), Igor Ostrovskiy (Private Investigator), Rolando Solorzano (US Marine), Mark Wagner (Project Architect for 9/11 Museum & Memorial), Michael S. Bell, PhD (COL, USA, Ret.) (Executive Director of the Institute for the Study of War and Democracy), David Waggonner (Resiliency Architect).

Location: Louisiana (New Orleans, Plaquemines Parish)

Year: 2021–2022

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com