Country X

Abstract

Country X investigates the spatial, ecological, and cultural systems underlying the Tuscarora Nation and broader Haudenosaunee territories. Through transcripts, field discussions, and collective mapping between Architecture Field Lab and Indigenous collaborators, the project reconstructs how movement, language, and ecology constitute political space. What begins as an interview archive evolves into an analytic cartography of survival—linking pre-colonial migration routes, watersheds, and trade paths to the modern consequences of reservation borders, resource extraction, and repatriation policy. The study exposes how the apparatus of mapping—once a tool of appropriation—can be redirected toward restitution and continuity. By examining borders as ecological rather than geometric constructs, the project reframes territory as a reciprocal relation between community and environment rather than a static plot of land.

Context

Country X arises from a series of interviews conducted with members of the Tuscarora Nation and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, interpreted alongside a research studio exploring Indigenous spatial systems across North America. The dialogue reveals how borders and identities are historically produced through layers of movement—voluntary, forced, and adaptive. The Tuscarora, the sixth Nation to join the Iroquois Confederacy, migrated north from present-day North Carolina to the Niagara region during the early eighteenth century following war and colonial displacement. Yet their oral histories stretch far deeper in time, recounting crossings that pre-date written record and link migration to cycles of ecology rather than conquest.

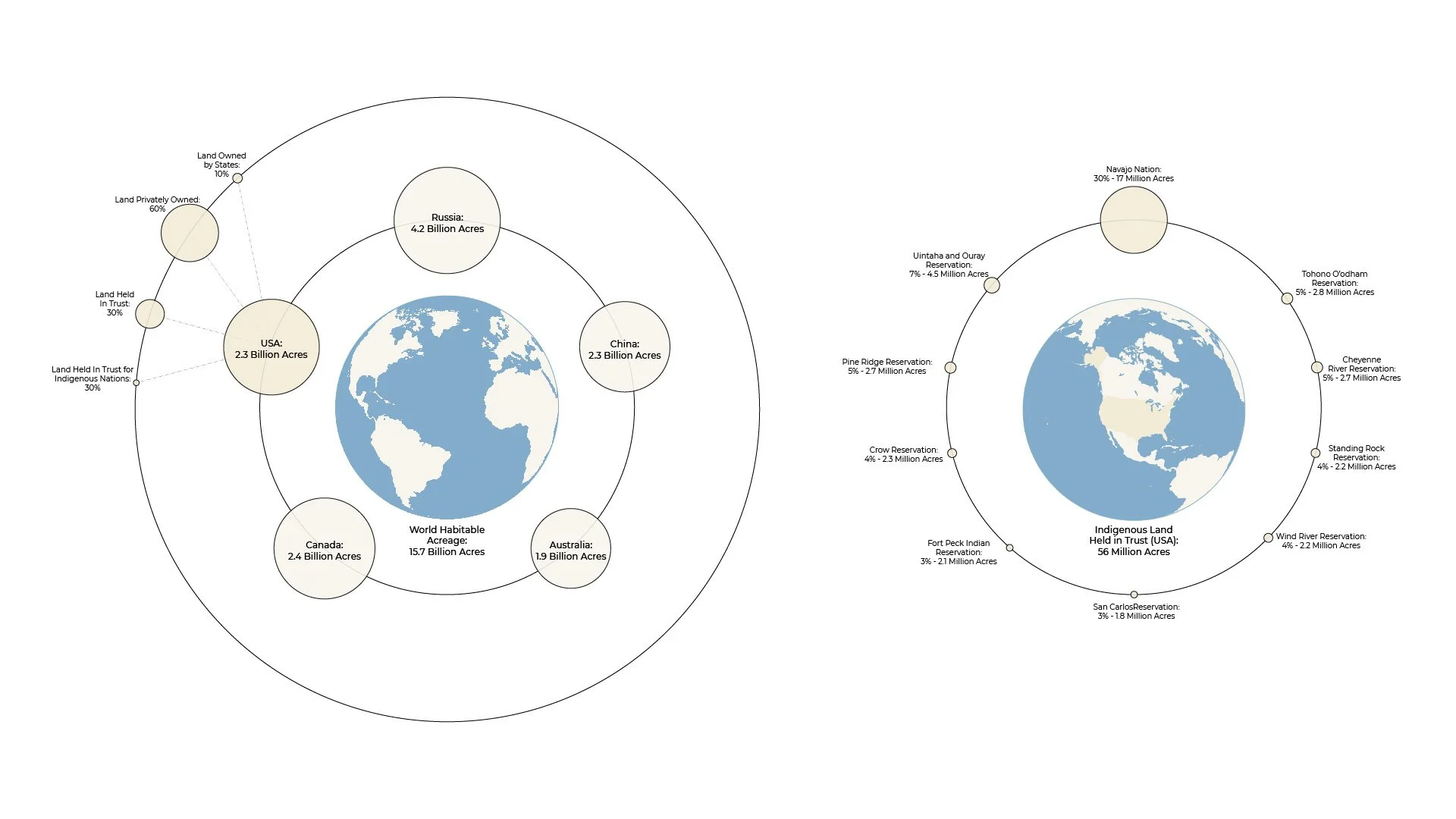

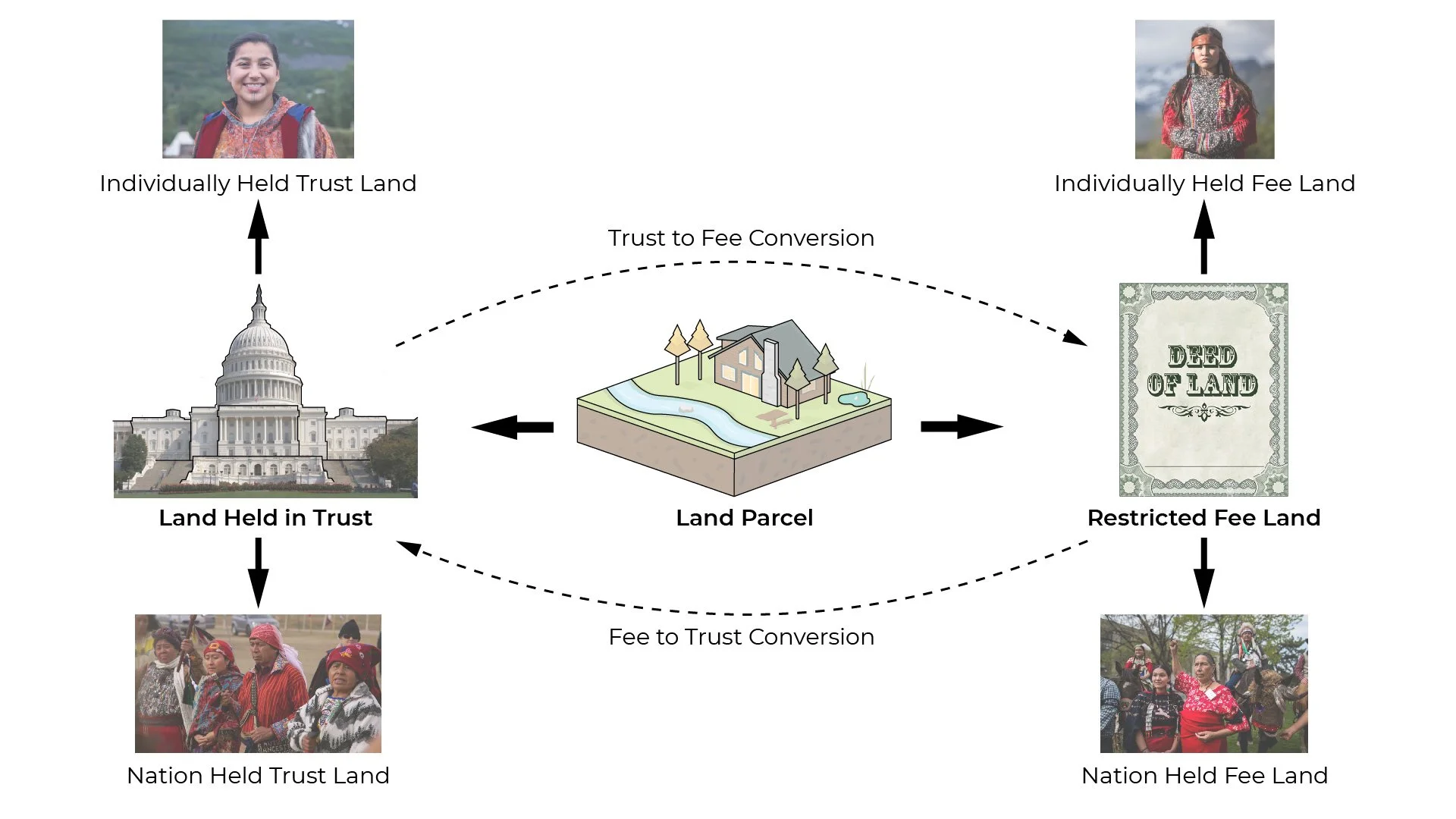

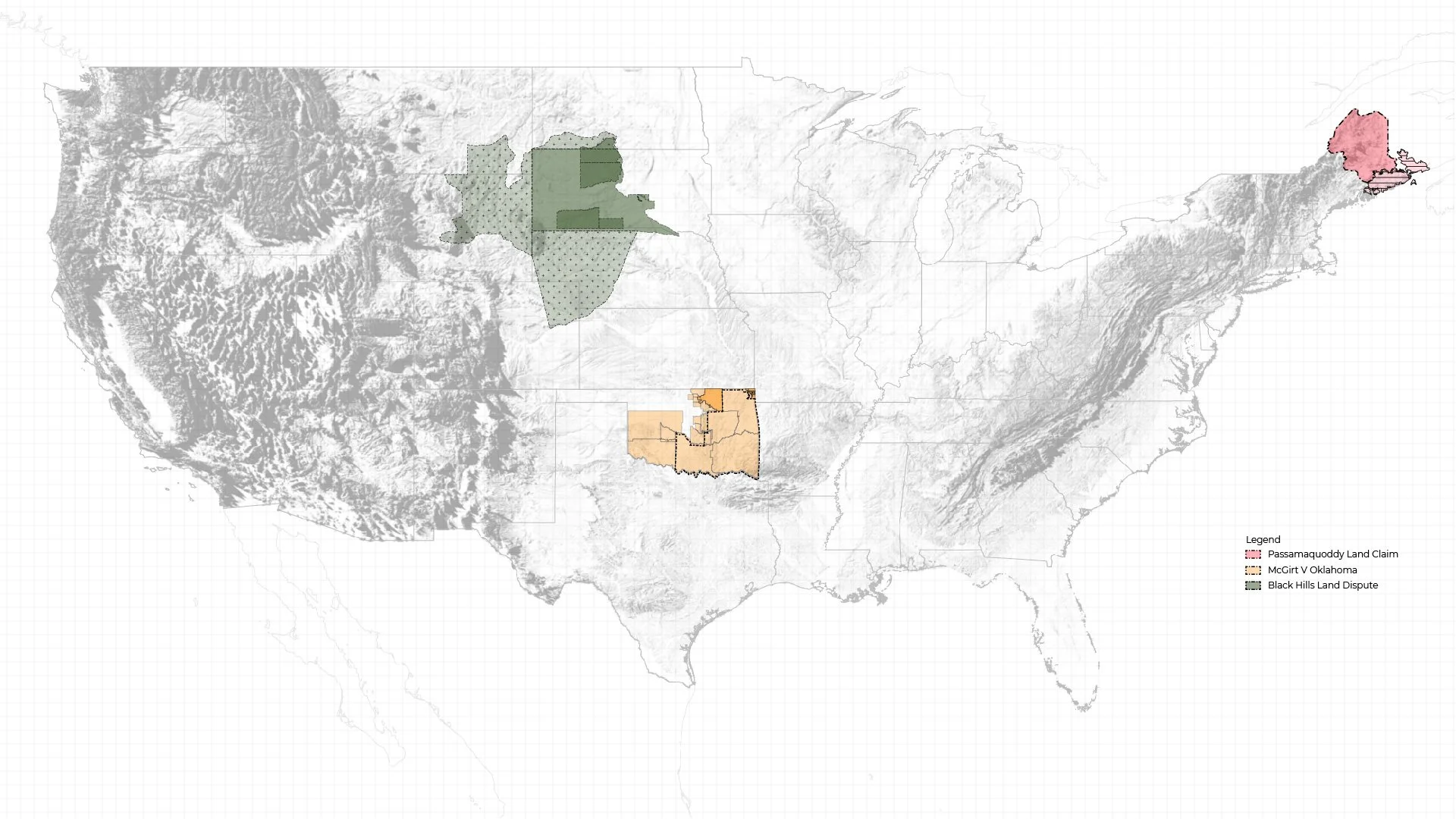

The contemporary reservation emerges as a remnant of this layered geography. The transcript exposes how the imposed borders of reservation life contrast with earlier fluid territories defined by rivers, hunting grounds, and seasonal cycles. These natural borders—watersheds, migration paths of fish and birds, the patterning of forest and soil—once regulated coexistence between people and environment. In contrast, the colonial grid and later legislative acts, such as the 1887 Dawes Act, abstracted these relations into parcels and quotas. The policy reduced Indigenous territory in the United States by more than 90 million acres, re-defining communal land as alienable property. What had been a shared ecological system became a fragmented legal landscape.

The research traces how this spatial disassembly paralleled cultural suppression. Boarding-school programs, exemplified by Carlisle Indian School and Thomas Indian School, aimed to erase Indigenous language and memory. Children were removed from their families, punished for speaking their language, and re-socialized into foreign codes of behavior. The impact was intergenerational: loss of linguistic continuity, disconnection from ecological knowledge, and trauma embedded within family structures. By examining these spatial and cultural erasures together, Country X positions architecture and cartography as instruments not merely of description but of governance.

At the same time, the narrative reveals counter-currents. Community initiatives for language revitalization, ecological restoration, and cultural mapping signal re-emergent forms of agency. The Tuscarora experience becomes a lens for examining how spatial knowledge—river navigation, seasonal burning, stewardship of fisheries—re-enters contemporary design and environmental management. The notion of Country X extends beyond one nation: it denotes a conceptual terrain where territory, memory, and system overlap. The project situates Indigenous spatial epistemologies as vital to understanding resilience under climate pressure, re-aligning spatial design with reciprocity rather than extraction.

Methods

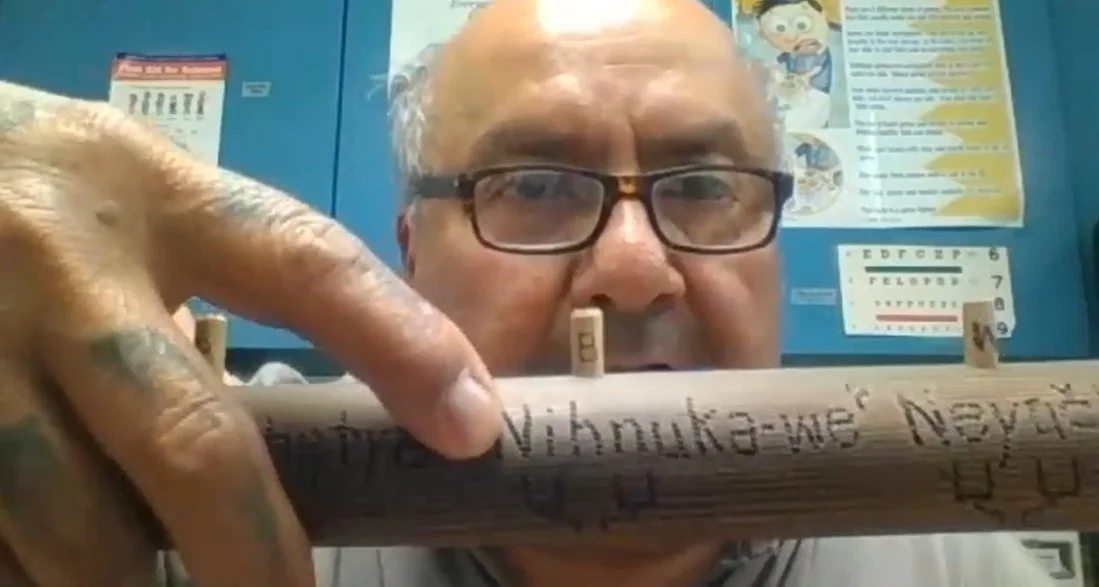

The research follows an investigative logic grounded in dialogue, translation, and mapping. Primary material includes interview transcripts, oral histories, and workshop documentation from collaborative sessions between Studio STIGSGAARD, architecture students, and Indigenous representatives. Each conversation is treated as both testimony and data—evidence of lived systems rather than anecdote.

The analytic procedure unfolds in four steps:

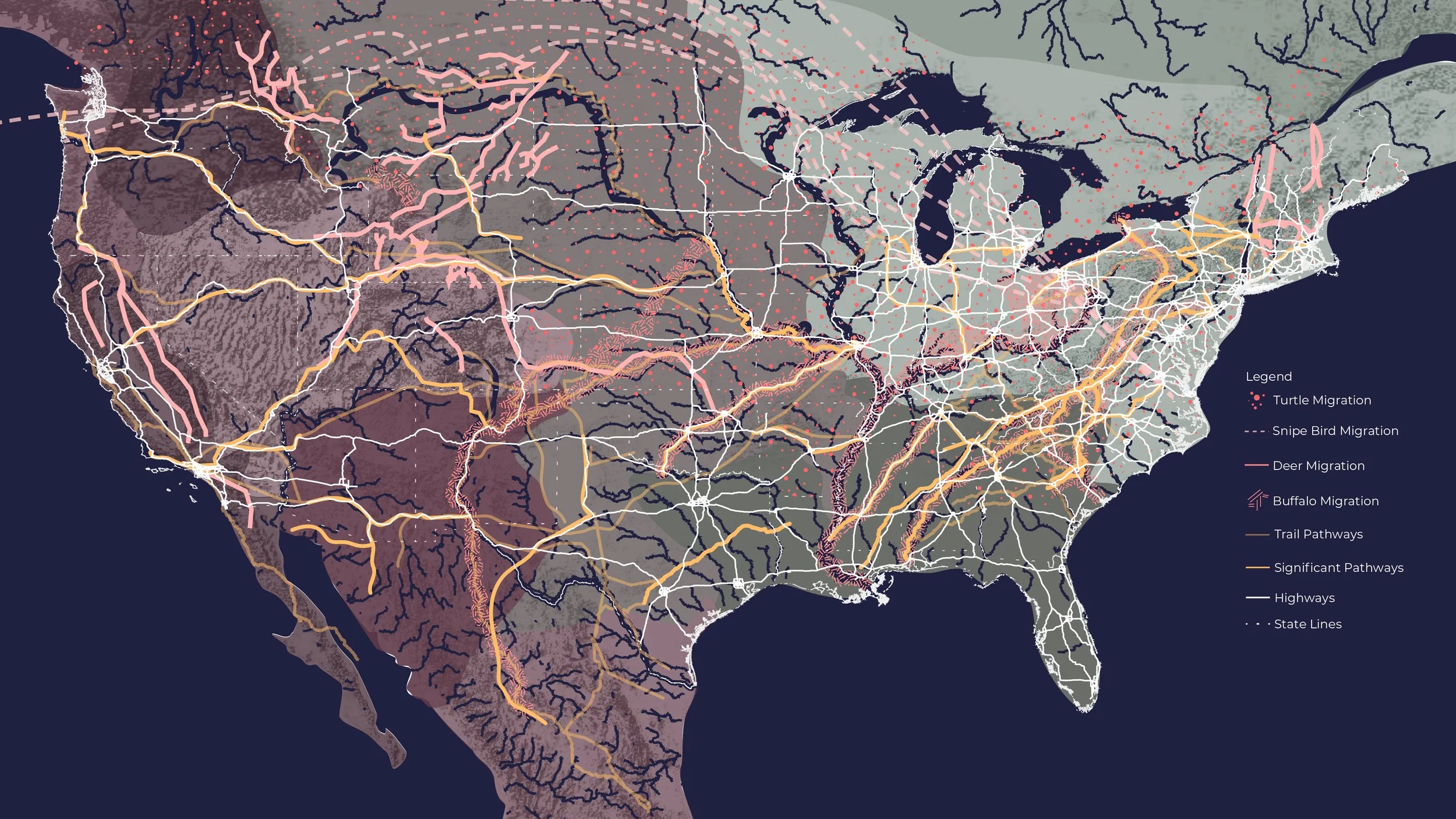

1. Spatial Reconstruction. Verbal accounts of migration, subsistence, and ecology are transcribed and translated into spatial sequences. Natural borders—rivers, forests, and watershed boundaries—replace cartographic lines as organizing structures. Historical routes such as the “Iroquois Highway,” later overlaid by the New York State Thruway, are mapped to reveal how colonial infrastructure followed pre-existing Indigenous pathways.

2. Temporal Stratification. The timeline of displacement—from the Tuscarora migration northward, through the Dawes Act land reductions, to boarding-school assimilation—is diagrammed as cumulative rather than linear. Each episode modifies territorial logic: from movement aligned with ecology to immobilization within surveyed plots, and finally to renewed mobility through cultural recovery.

3. Cultural Systems Analysis. Themes such as language loss, repatriation policy, and environmental rights are examined as spatial phenomena. The research correlates educational policy with spatial confinement, identifying how schools, museums, and cemeteries form a distributed infrastructure of control. Conversely, acts of repatriation and language teaching are read as architectural operations that reopen circulation between objects, stories, and people.

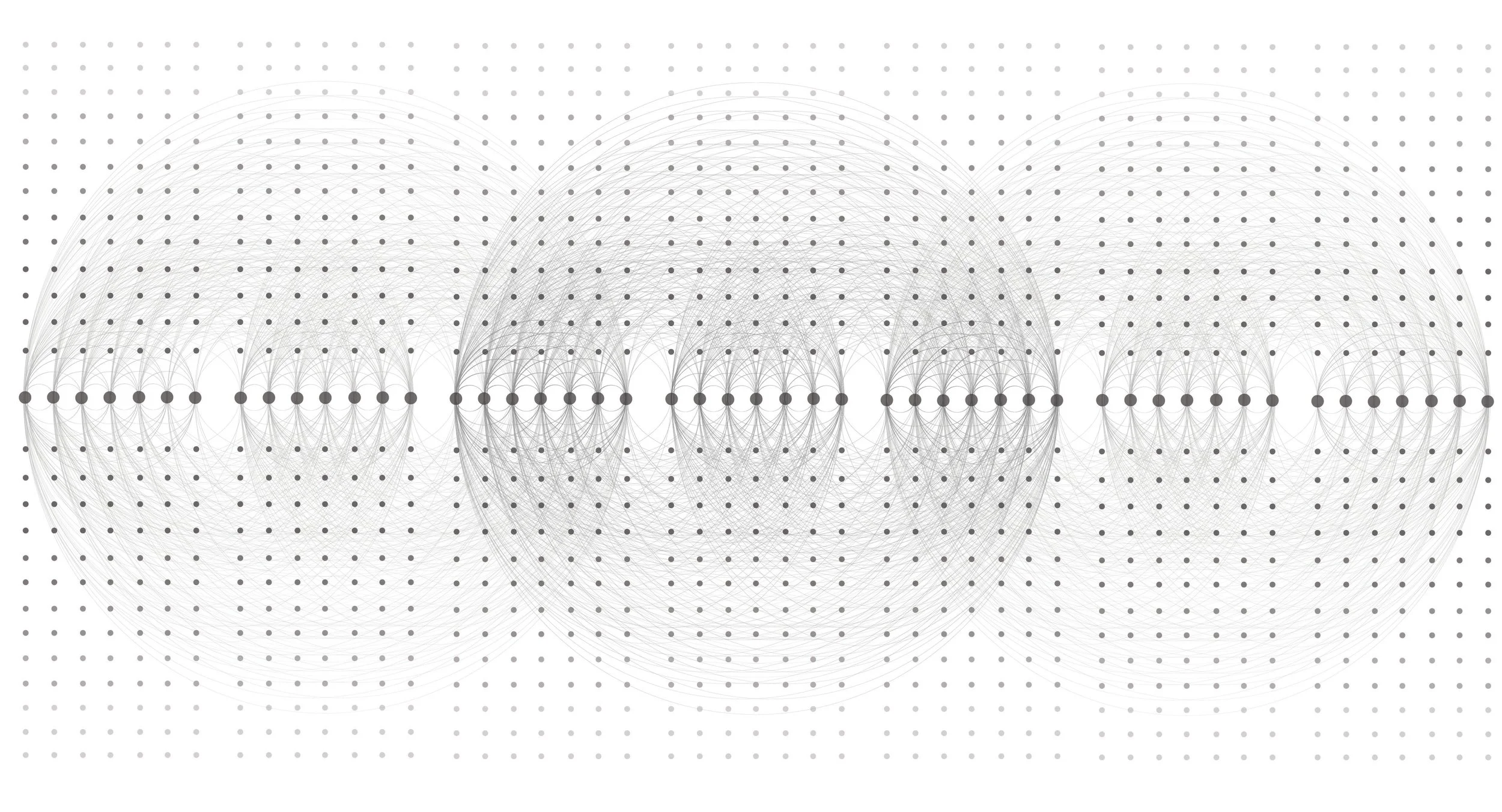

4. Cartographic Synthesis. The project re-maps the Tuscarora world through layered diagrams combining topography, hydrology, linguistic geography, and oral narrative. Each layer is verified through archival sources, oral confirmation, and ecological datasets. The resulting maps do not represent ownership but relation—how ecological cycles correspond to human practice.

Throughout, the research maintains transparency of method: every inference is linked to its source and degree of certainty. Where data is fragmentary, the analysis privileges continuity of meaning over precision of coordinates. This allows the cartography to remain truthful to Indigenous epistemologies that describe territory as a set of relations rather than a bounded field.

Findings / Reflection

Ecological Borders. Testimonies emphasize that natural borders—watersheds, migration corridors, forest ecotones—once defined community rather than divided it. These borders are porous, negotiated through stewardship and ritual. Reinstating them as planning frameworks could realign governance with ecological reality. A watershed-based polity would bind inhabitants to shared responsibility for water quality and forest management, transforming environmental protection from policy to practice.

Language and Space. Language is revealed as a spatial instrument. Terms describing rivers, fish, and seasons encode operational knowledge—when to harvest, when to move, how to build. The suppression of language through boarding schools thus erased an environmental management system. Recent revitalization efforts, such as the Mohawk-derived verb-root method adopted by the Tuscarora, function as both linguistic and territorial reconstruction. Fluency re-activates maps that exist in words.

Migration as Continuity. The oral histories of “crossing the ice” and “the grapevine story” narrate origin and displacement not as rupture but as cyclic adaptation. Movement follows ecological opportunity: fish runs, growing seasons, and forest regeneration. Colonial interpretation misread this mobility as nomadism, justifying appropriation. By contrast, the research frames it as a systemic strategy balancing extraction and renewal. Design that recognizes seasonal occupancy and rotating land use could recover this sustainable mobility within contemporary planning.

Infrastructures of Control. The study exposes how colonial infrastructure—roads, schools, museums—replaced ecological and cultural connectivity with administrative control. The Dawes Act transformed communal land into alienable property; boarding schools replaced oral transmission with institutional discipline; museums detached cultural artifacts from their ritual ecosystems. Each structure re-routed flows of value and knowledge away from Indigenous agency. Mapping these as a single infrastructural network clarifies how policy materializes as space.

Repatriation and Agency. The repatriation committees described in the interviews re-invert this flow. By retrieving ancestral remains and cultural artifacts from museums and universities under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Indigenous nations re-establish custodianship over both material and meaning. The process transforms storage into dialogue; documentation becomes a new architecture of return. Each repatriated object reinstates a circuit of reciprocity between institutions and communities, re-linking governance with ethics.

Environmental Reciprocity. Ecological stories centered on fish—especially the sturgeon—reveal how species function as indicators of systemic health. Industrial pollution of the Niagara River disrupted this relation, erasing both sustenance and ceremony. Restoration efforts illustrate the convergence of traditional ecological knowledge and contemporary environmental science: hydrological rehabilitation, pollution control, and species monitoring merge with ritual practice. The fish re-entering the river embody the return of relational balance.

Temporal Repair. Country X identifies temporal disjunction as a core spatial issue. The time scales of policy, ecology, and memory diverge—legislation operates in decades, ecosystems in centuries, and trauma across generations. The project proposes “temporal mapping” as a design tool aligning these scales. By sequencing restorative acts—language classes, water stewardship, artifact return—within shared calendars, communities regain rhythm after imposed interruption.

Mapping as Ethics. The final reflection considers mapping not as representation but as negotiation. Each map is a statement of relation: who defines territory, who maintains it, who benefits from it. When maps acknowledge Indigenous epistemologies—narrative direction, relational naming, cyclical time—they become ethical documents. The process of co-mapping in the studio thus becomes performative: students and community members produce shared knowledge while re-situating design within history’s ongoing terrain.

The project concludes that architecture’s role in Indigenous territory is less about construction than about mediation. Through careful translation between systems—ecological, linguistic, administrative—it can transform static heritage into dynamic agency. Country X demonstrates that recovering Indigenous mapping practices does not simply correct history; it establishes new frameworks for living systems governance at a planetary scale.

Credits

Architecture Field Lab Research Program: Lesley Epps, Jasmine Perez, Evana Said, Caroline Ho, Katherine Tenman, Camilla Thomas, Jose Zacarias, Camilla Thomas, Krystian Sidorski, Katherine Tenman, Carlos Almeida, Evan Craig, Paolo Ruiz, Krystal Hernandez, Angela Njoroge, Hanna Dinaburg Nozdrin, Ashley Echevarria, Noor Ain, Hajar Alrifai, Fernando Aparicio, Tiffany Gonzalez, Mehrose Naeem, Jasmine Perez, Brendan Smith, Taylor Mastrota (Spitzer School of Architecture)

Collaborators: Tuscarora Nation representatives; Chief Tom Jonathan, Angela Jonathan, Vince Schiffert, Clifford Jacobs, Robert D’Alimonte. Dioganhdih Hall (Mohawk of Akwesasne), Michael Delgado (Quechua), Justin Guthrie (Navajo), Alexandra and Luis Checa, Tom Tureen Land rights Lawyer, Prof. William Brinkman Clark UNAM, Prof. Mary C. Churchill, Prof. Hillary Brown, Vic Muniz (Artist), Peter Funch (Artist), Rufus Tureen (Artist)

Location: New York State / North Carolina / Haudenosaunee Territories

Year: 2022–2025

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com