Coastal Resiliency

Abstract

Coastal Resiliency examines how cities translate climate risk into spatial and institutional change. The research pairs two New York–area laboratories: Lower Manhattan’s East River Waterfront, where a multi-agency plan reconceives the FDR Drive’s underside as a canopy for public life and continuous access to water, and Nassau County’s South Shore, where “Living with the Bay” proposes a buffered-bay approach that integrates marsh restoration, sediment management, and upland stormwater relief. Across both contexts, the project treats the shoreline as a dynamic interface—geological, civic, and economic—requiring typological clarity and administrative coordination. It studies edge systems (esplanades, piers, slips, surge barriers, living shorelines), governance instruments (risk prioritization, procurement criteria, M/WBE and Section 3 goals), and scalar integration (regional, sub-regional, site). The inquiry advances a framework where design, ecology, and policy are mutually legible: pavilions and cladding under viaducts, re-spanned piers that improve tidal flow, marsh islands that attenuate waves, and ring levees tied to community assets. The work argues for a resilient urbanism rooted in reciprocity—between land and water, infrastructure and habitat, community and state—delivered through projects that can be built now but adapt to future conditions.

Context

Lower Manhattan’s south-facing East River waterfront is a historical armature of trade, infrastructure, and civic identity. After decades of disconnection, a city–state–community coalition developed a plan to reclaim this edge as public realm—linking Battery Park to East River Park with a two-mile esplanade, new pavilions beneath the FDR Drive, enhanced lighting and sound attenuation, and access to rebuilt piers and restored slips. The plan reframes the viaduct’s underside as a canopy supporting cultural, commercial, and recreational programs, bringing activity to the water’s edge while improving safety and permeability across South Street. Its collaborative method—dozens of public meetings and a phased set of “Foundation Projects”—anchors design in community process and multi-agency feasibility.

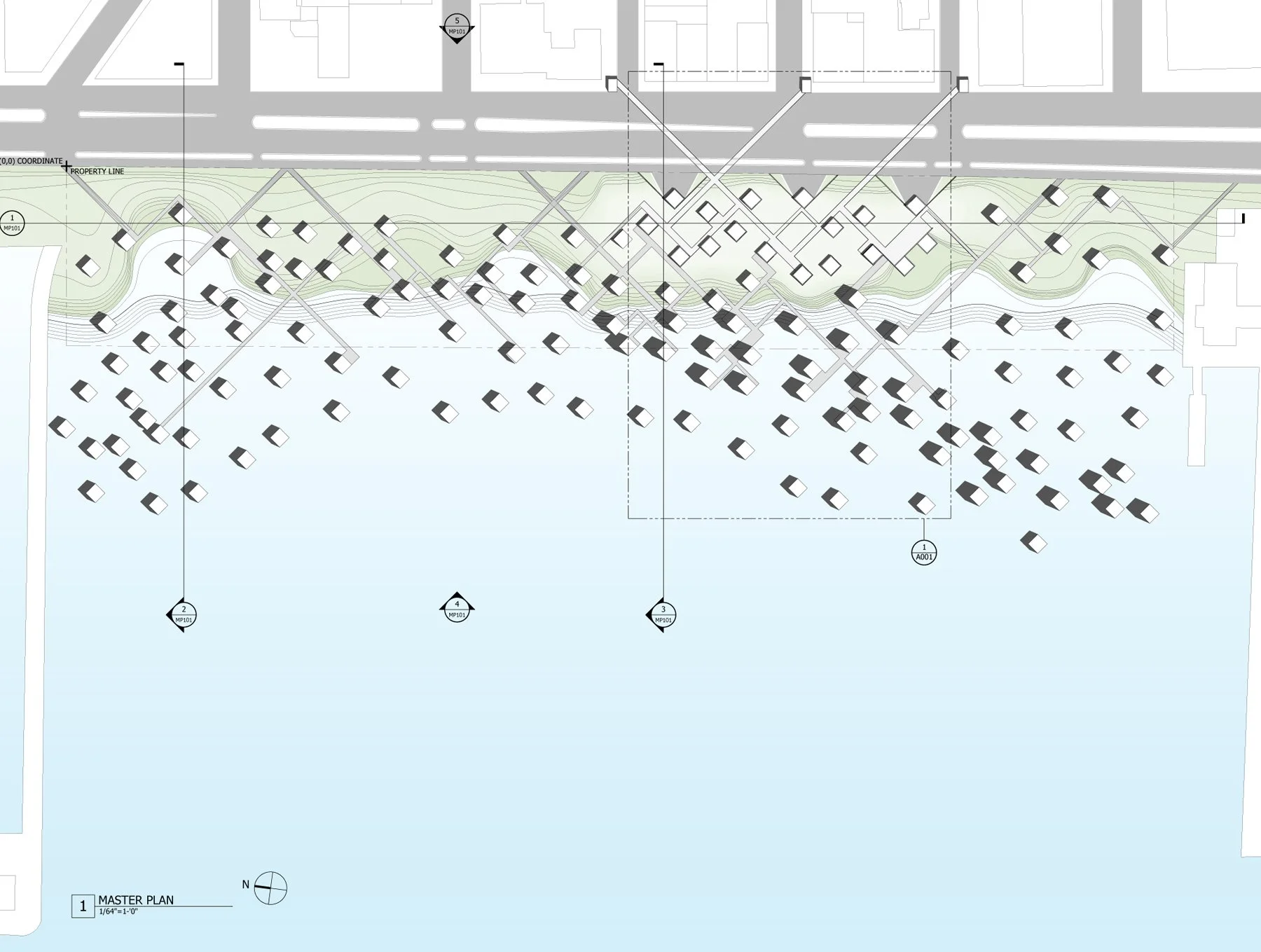

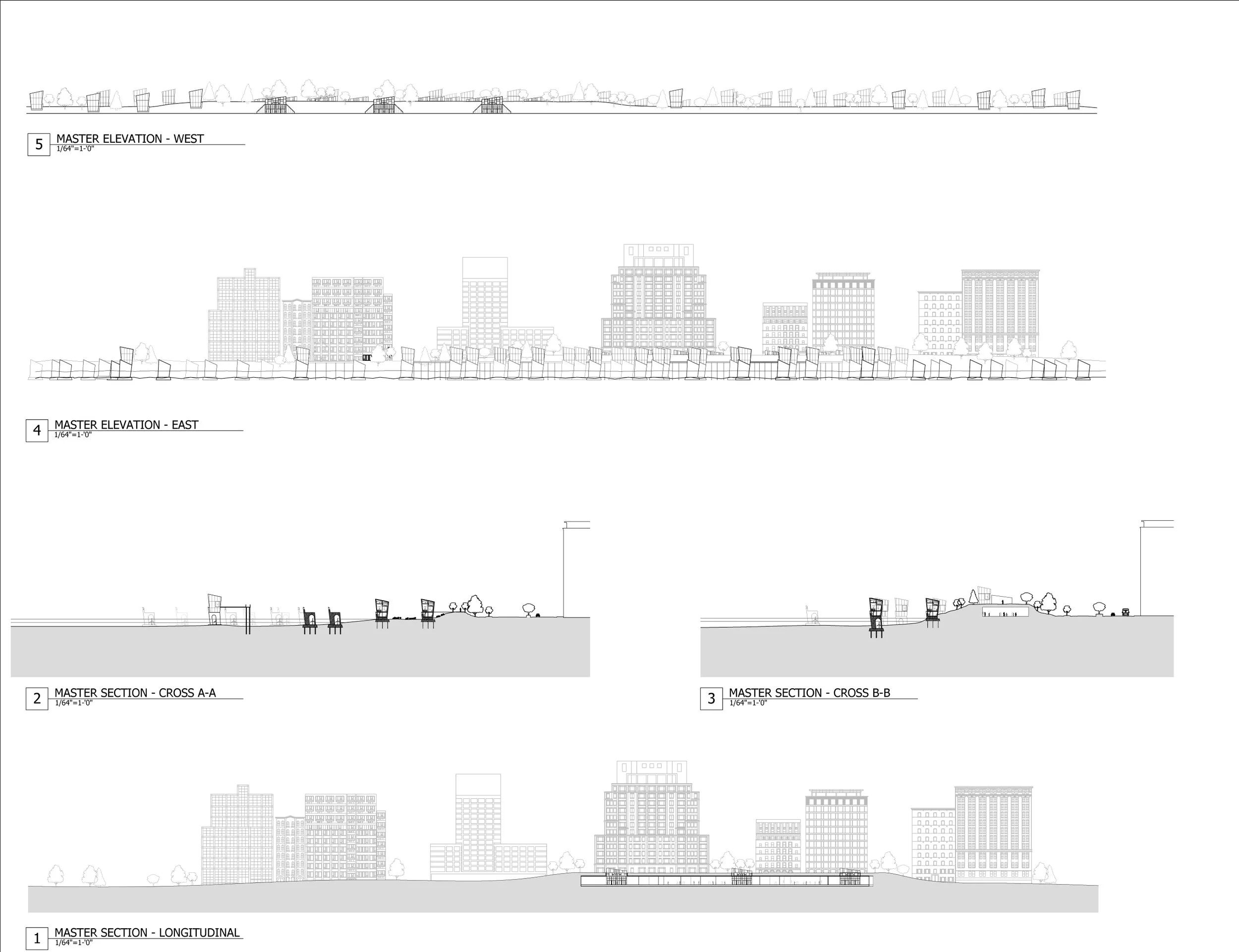

The waterfront proposals specify components and sites that function as typological proofs. Esplanade modules—benches, railings, arbors, planters, and reinforced concrete paving—create a continuous identity. Pavilions under the FDR are conceived as small, transparent buildings that open in warm weather and keep view corridors to the river unobstructed; cladding improves acoustics and legibility under the viaduct. Piers shift to long-span structures with wider pile spacing to restore tidal exchange and reduce sedimentation; their Vierendeel-truss sections allow program below and parkland above. Slips (e.g., Peck Slip) are reinterpreted as civic rooms that recall historic water—seasonal pool/ice rink—while clarifying pedestrian and vehicular movements. Gateways at the Battery Maritime Building and the East River Park connection resolve broken links through regraded plazas and reconfigured traffic. Together, these elements act as an “edge system” where access, ecology, and maintenance protocols are explicit.

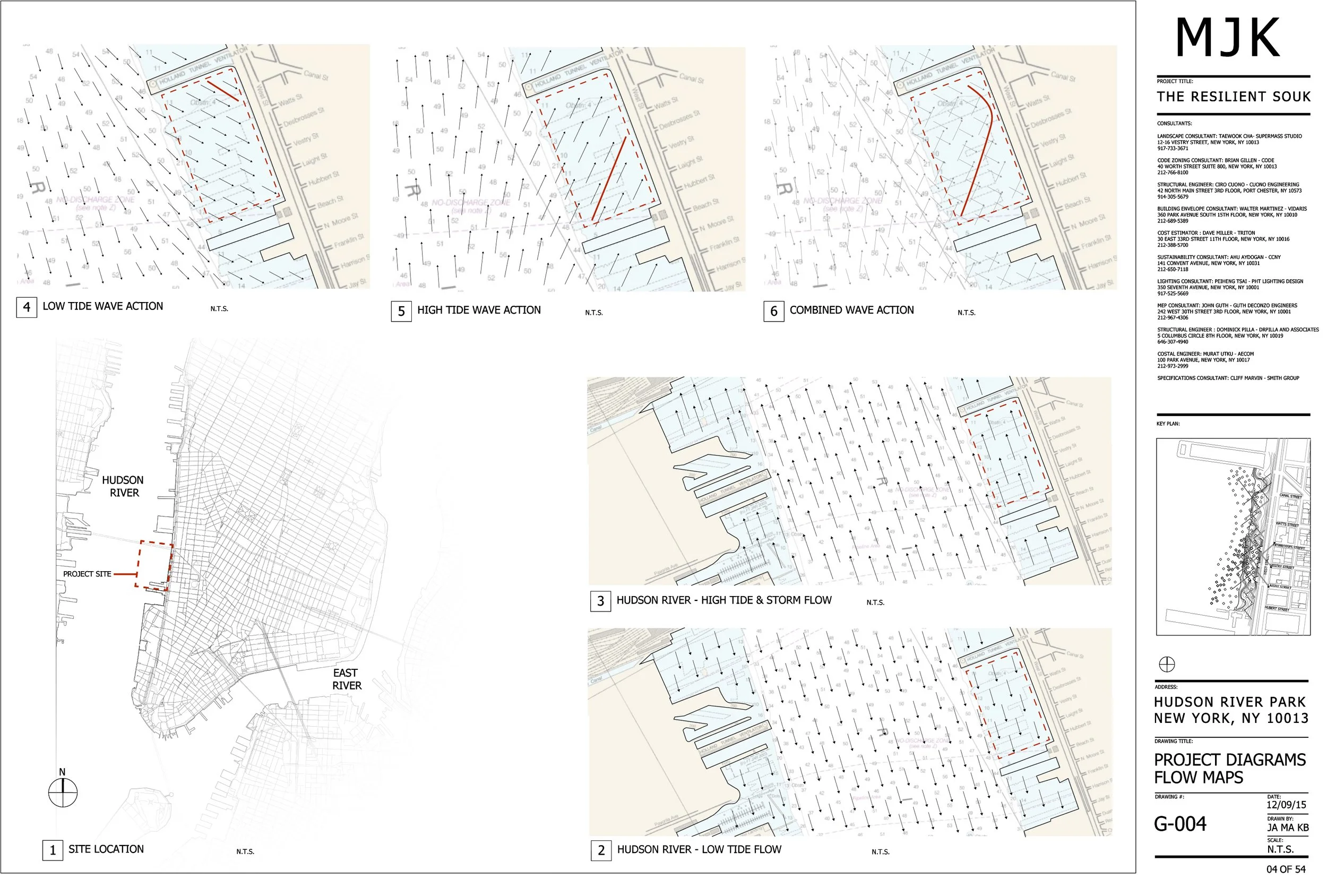

In parallel, Nassau County’s South Shore faces layered risks: storm surge (Hurricane Sandy), gradual sea-level rise, stormwater backflow, and wastewater-driven eutrophication. Here, the Rebuild by Design team proposed a “Buffered Bay” rather than a permanently closed or fully open system. The buffered strategy integrates near-term and long-term measures across region, sub-region, and site: bayfront dikes with retention parks to protect critical infrastructure; sediment engines and tidal-prism adjustments to sustain barrier-island and ocean-shore morphologies; marsh-island chains and ring levees to reduce wave energy and bolster ecology; and upland “green corridors” to decouple stormwater from river outfalls. This framework emerges from a broad coalition—agencies, municipalities, civic groups, universities—and advances governance as resilience infrastructure.

Finally, the City’s “Raise Shorelines Citywide” initiative situates coastal protection within procurement and equity. Its first-phase program outlines strategies—raising coastal edges, minimizing upland wave zones, storm-surge protection, and improving design/governance—paired with an area-prioritization method keyed to storm-surge probability, “floodable FAR,” critical infrastructure, and vulnerable populations. Tasks include building a citywide shoreline database, selecting sites for concept design, and aligning delivery with CDBG-DR mandates and M/WBE and Section 3 participation—evidence that resiliency also depends on how projects are made.

Methods

1. Systemic mapping and typology definition

The study maps hazards (surge extents, SLR scenarios, stormwater backflow), program networks (mobility, pavilions, slips), and ecological regimes (tidal exchange, marsh loss) to define edge typologies. At the East River, this yields an esplanade–pavilion–pier–slip system; at the South Shore, ocean shore/barrier island/marsh/uplands strategies form an integrated kit of parts.

2. Structural–ecological calibration

Design elements are tested for hydrologic performance and habitat effect. Long-span pier bents with wider pile spacing improve flow and reduce scouring; reef-ball additions expand habitat. Marsh islands and ring levees are positioned to attenuate waves while improving ecological function; sediment engines and over-wash facilitation keep barrier morphologies adaptive. The waterfront cladding under the FDR is positioned as a noise and lighting intervention to extend safe use hours.

3. Governance and delivery as design media

Procedures are modeled alongside forms. The Raise Shorelines program articulates risk-based prioritization, a citywide shoreline database, and procurement sequences (study → concept → construction documents → build), with equity frameworks (M/WBE, Section 3) embedded from the outset. Rebuild by Design’s tri-scalar approach coordinates regional policy with local pilots, while East River’s Foundation Projects phase scope to feasibility and stewardship.

4. Stakeholder choreography

A continuous public process—community boards, civic groups, and technical committees—shapes siting, program, and thresholds. This method builds operational legitimacy and aligns maintenance responsibilities with use. The result is a governance ecology where agencies, advocates, and neighborhoods co-produce resilient edges.

Findings / Reflection

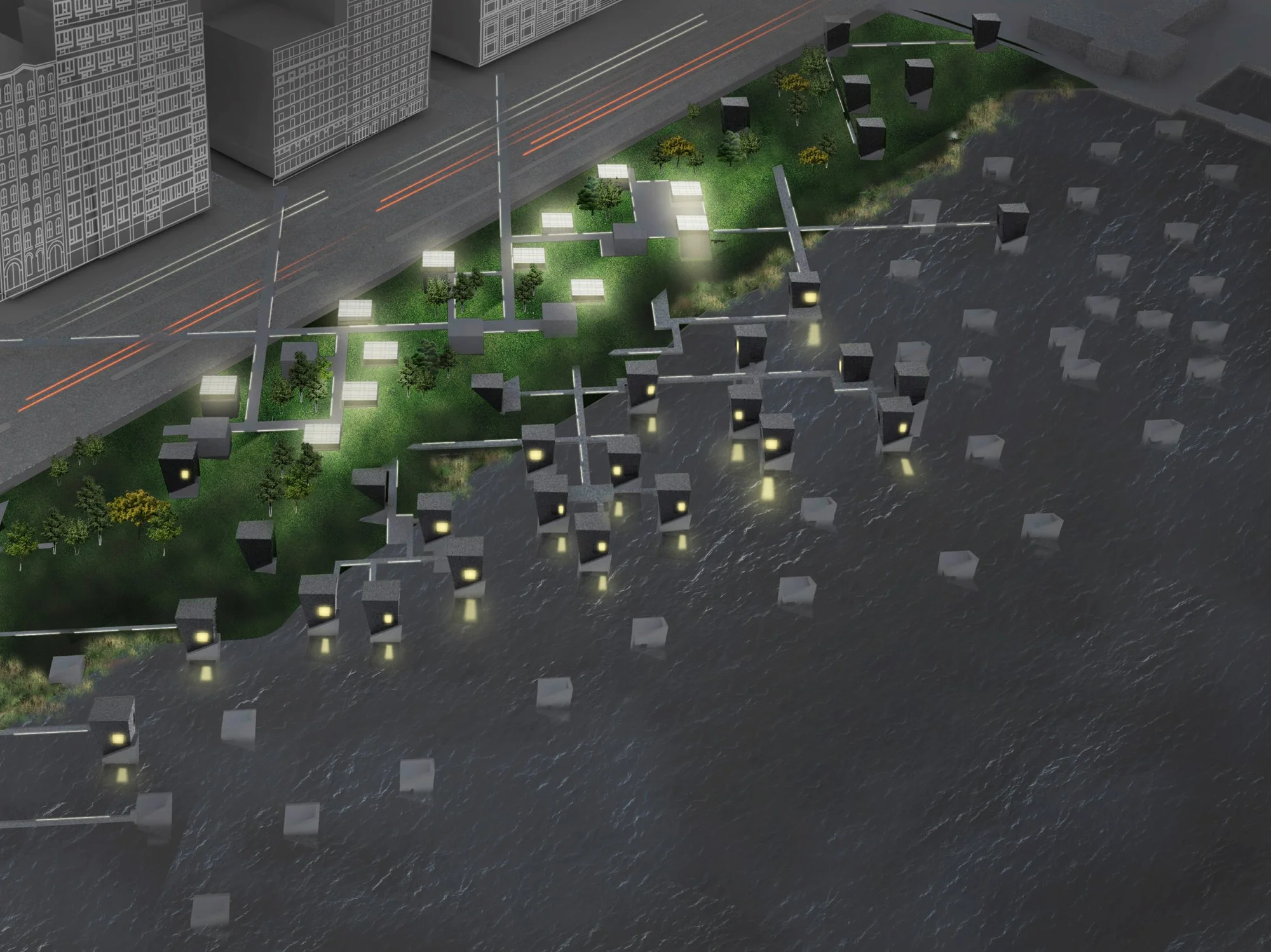

1. Resilience resides in edges that do multiple things well

Edges that only protect tend to sever public life; edges that only entertain invite risk. The East River system demonstrates how an esplanade can be both infrastructure and civic room: pavilions activate the underside of a highway without sacrificing throughput; cladding makes a harsh viaduct recognizable and safe; slips acknowledge memory and direct circulation; and piers become environmental engines as much as promenades. Typological clarity enables maintenance and policy: each component carries a clear function (access, attenuation, habitat, revenue) and a steward.

2. Hydrology must be designed as a reciprocal system

At site scale, shifting to longer pier spans with fewer piles reduces sedimentation, restoring exchange; at bay scale, marsh islands and ring levees provide friction and storage; at shoreline scale, raised edges couple with wave-minimization and surge management. These systems must be read together: reducing backflow in uplands (green corridors) matters as much as ocean-side nourishment. Reciprocity—between engineered and living elements—expands performance without overbuilding.

3. Time is a design parameter, not a constraint

Raise Shorelines and Buffered Bay treat delivery in phases: near-term “no regret” moves (edge-raising, pilot marshes, retention parks) prepare for long-term sea-level rise. The East River plan’s Foundation Projects establish an operable baseline (continuous path, basic amenities) that can absorb future programs. Designing for temporalities—daily usage cycles under a viaduct, seasonal slip programming, decadal marsh accretion—turns resilience from a one-off investment into a calibrated, revisable practice.

4. Governance is the hidden structure of resilient form

Risk heat maps and prioritization matrices determine where to act and when; procurement criteria, equity requirements, and technical standards determine who delivers and benefits. The East River project succeeded in part because of a dense, iterative public process that reconciled differing neighborhood identities without imposing a single image. Rebuild by Design’s coalition across municipalities counters “home rule” fragmentation, allowing measures that work hydrologically rather than politically. Architecture’s ethical task here is to expose governance as legible infrastructure—visible in plazas, in pavilion contracts, in the selection of sites whose vulnerabilities are social as well as physical.

5. Pilots should be specific enough to learn from and general enough to transfer

Pier 15’s two-level section demonstrates how structure can be both program and park; Peck Slip’s seasonal pool/skating plane ties heritage to present use; a Jones Inlet sand engine tests sediment distribution; a Freeport ring levee/park reframes protection as public amenity. Each prototype is sited to local conditions but framed as a typology—transferable to other slips, other piers, other bayfronts—so that knowledge accumulates across the harbor system.

6. Equity is a performance criterion

Raise Shorelines binds coastal projects to CDBG-DR mandates and participation goals that recognize who is most exposed and who earns from the work. Prioritization includes “floodable FAR,” critical infrastructure, and vulnerable populations; Section 3 and M/WBE plans push benefits into the local economy. Resilience therefore includes procedural justice: whose neighborhoods receive early investment; whose businesses fabricate the railings, pavilions, and reef modules; who maintains the systems over time.

7. A buffered logic avoids brittle extremes

The Buffered Bay strategy rejects both fully open and fully closed solutions: operable systems, naturalized edges, and sediment-aware interventions produce a resilient middle ground that preserves ecological quality while reducing harm. This approach aligns with the East River’s evolutionary, not prescriptive, development: build the connective tissue first, then iterate. The shared lesson is to favor systems that learn—edges that register waves as energy sources (wind, light), pavilions that adjust to use, marshes that grow with sediment—to absorb change rather than resist it outright.

8. Design is an ethic of exposure

Across all cases, resilience improves when operations are visible. Under-viaduct cladding that reveals structure and lighting, transparent pavilions that show activity and stewardship, railings that integrate fishing holders and interpretation, and marsh parks that display water levels and nutrient cycles—all make the public co-authors of coastal care. Exposure turns maintenance into culture and turns risk into shared knowledge.

Credits

Architecture Field Lab Research Program: Eleni Christoforides, Sam Davidowitz-Neu, Alexandra Diaz, Ana Garcia, Marcos Gasc, Ben Grinblatt, Meisha Guild, Nancy Kelleher, Peter Kostelov, Marina Santos, Matthew Shufelt, Berk Sonmez, Gavi Wilcox

Collaborators: NYC Department of City Planning; NYC Economic Development Corporation; SHoP Architects; Richard Rogers Partnership; Ken Smith Landscape Architect; Buro Happold; Langan; ERA; URS; Interboro Partners and RBD team partners (Deltares, H+N+S, CUP, NJIT, et al.); community boards, civic and environmental organizations (representative).

Location: Lower Manhattan, East River Waterfront; Nassau County South Shore (Jones Inlet, Long Beach, Freeport, Rockville Centre, East Rockaway)

Year: 2015–2016 (research and proposals)

Contact: info@studiostigsgaard.com